Where Is God in This Smoke?

Today, the news will be monopolized by Donald Trump’s indictment in Miami. Cable news channels will offer wall-to-wall coverage of the event. Viewers will wait anxiously to see if flag-waving, camo-clad partisans will manage to stir up a revolt like the one in Washington on January 6, 2021.

And what will be missed in today’s headlines is the specter of massive fires in Canada’s Quebec Province. The fires are tragic enough. But with all the drifting smoke, there will also be millions on America’s densely populated East Coast choking on dangerously unbreathable air.

Imagine the irony of a TV news anchor donning a left-over N-95 mask, struggling to drive to her television station, coughing, and with watery eyes laboring to report on the court drama Miami. All the while she’s ignoring the truly apocalyptic reality just outside her air-conditioned building.

This latest media circus from Trump World has not distracted Pulitzer Prize winning journalist, Chris Hedges. His column this week offered the starkest interpretation of Canada’s massive fires that I’ve read in a while. These blazes are yet another wake-up call that drags us again into that terrifying truth we can only face for the shortest period before we return to some lesser concern. Put bluntly the flames and smoke remind us that humanity is in deep trouble. Extinction is not too drastic a word for humanity’s prospects.

Hedges is not only a seasoned left-leaning journalist with several books to his name, he’s also a Presbyterian minister and the son of a Presbyterian minister.

I’m a reader of much of his work. In many columns, he openly acknowledges his theological education at Harvard Divinity School. In this week’s column, however, Hedges makes no mention of God. Neither does he give a Christian interpretation of the fires, even though many have described such catastrophes as taking biblical proportions.

All he says explicitly of a spiritual dimension is this:

The hardest existential crisis we face is to at once accept this bleak reality and resist. Resistance cannot be carried out because it will succeed, but because it is a moral imperative, especially for those of us who have children.

Chris Hedges

What a disappointment—resistance because it’s better than resignation. I’m not inclined to criticize Chris Hedges for not giving more hope for this terrifying moment that all of us are in. He’s already done good writing here in laying out the problem.

And he still leaves us wondering, “Where is God?”

Despite Hedges silence on explicit hope, the world he describes and the forthrightness with which he says our condition reverberates with biblical situations of total wipeout. Where else do we read of such hopelessness other in the stark frankness of writings like this one and in the words of scripture? These are words of biblical size to confront us with a crisis of biblical size.

Consider this from the Old Testament prophet, Jeremiah:

I looked on the earth, and lo, it was waste and void; and to the heavens, and they had no light. 24I looked on the mountains, and lo, they were quaking, and all the hills moved to and fro. 25I looked, and lo, there was no one at all, and all the birds of the air had fled. 26I looked, and lo, the fruitful land was a desert, and all its cities were laid in ruins before the Lord, before his fierce anger.

Jeremiah 4.23-26

It’s on this point that I propose that Biblical faith might speak with our desperately threatened generation. When we “get” the depth of the crisis we may have an ear for these ancient words that also seem to “get” it.

We’re in an apocalypse. Where better to learn about living in apocalypse than the book that gave us the concept?

Hedges leaves me longing for hope. And the very longing for hope itself carries a bit of hope. God speaks the language of climate catastrophe. And the Bible carries a sturdy hope in the face of catastrophe.

The civilization ending potential of global warming has overcome us very quickly and the recognition of biblical hope in the face of such a crisis has been slow in emerging. But hope is there. It exists in the texts of creation which we find in the first chapters of Genesis and threading through the Bible. It exists in fresh considerations of Jesus’ cross and resurrection and the scope of redemption.

What follows are four observations from the creation stories in Genesis and beyond that suggest how God is present in climate change and specifically the Canadian fires.

The World Belongs to God

This is so simple that it may not seem of much help when one is choking in a yellow world of smoke. The 24th psalm declares:

The earth is the LORD’s, and everything in it,

the world, and all who live in it.

Psalms 24.1

It is so simple that the first two chapters of Genesis omit to mention it. It’s as if God isn’t overbearing and forever reminding humanity that it all belongs to Godself. In turn, we forget the basic politics of the created order and treat the world like it was a lost wallet waiting for us to pick it up as our own.

Human societies have long ago ignored that people don’t own the world. Both in politics and business, people have schemed, fought, and died to occupy territory or own more stuff. Both capitalism and Marxism are preoccupied with who owns what. The focus of economics and politics is ever on “means of production,” the fruits of labor, the land, minerals, agricultural products, animals, and the laborers themselves.

One would never guess that, “The earth is the Lord’s and everything in it,” in the midst of a political campaign or a labor dispute or on an off-shore oil drilling platform. The idea of God’s ownership, when it crops up, is always an inconvenience. It reorients our attitude. The Apostle Paul, in giving advice in I Corinthians 10.26 about eating “unclean” foods quotes these words, and in doing so completely reframes the situation.

I’ve forgotten the source of this story, but a man walking down a street in London came upon another man beating his horse. The stranger intervened. He stood between the horse and the man with the whip. “Get out of the way, this is my horse,” yelled the owner, to which the other replied, “it’s God’s horse and I’m here to protect it.”

That the Earth is the Lord’s won’t clear the smoke. But it gives a framework for understanding what has gone so terribly wrong and what must be done.

God Isn’t All-Powerful

We’re accustomed to hearing and thinking God is controlling everything. To question God’s sovereignty and almightiness appears to signal grave confusion. If God created everything from nothing, itself an idea that is not as secure as I’ve long thought, then surely God reigns over what he created with total sovereignty.

I’m beginning to think that the know-everything and in-control-of-everything views of God’s character are distortions of the divine attributes. In turn, we miss understanding how wonderful God really is.

A fussy close reading of Genesis’ first chapter bears this out. I’ve heard it said that God was so powerful in creating the world that God simply spoke it into existence. I call this the poof view of divine creative power.

So, the creation verses in Genesis begin. “God said, ‘Let there be light’; and there was light.” Poof. Creation by the poof method.

The second day comes. “God said, ‘Let there be a firmament.’” But instead of saying, “and it was so,” the text says, “and God made the firmament.” It is as if the second day was a little less awesome than the first day and the poof of light.

This sense that the poof method is running out of steam continues through the next few days. In fact, the need to have multiple days suggests that the creator doesn’t have a single poof word that brings the Universe into being or that the creator intentionally wants to let the creation be a time-consuming process.

Curiously, the creator delegates some of the creative work. Let the earth bring forth vegetation and let the waters bring forth swarms of living creatures.

The general impression is that the story of creation begins as decree from outside, namely, God speaking things into existence. The mode of creation moves to sweaty hard work on the inside organizing existing material and getting others, mostly people, to pitch in and help.

If God were all-powerful, why wasn’t the entire universe brought into finished perfection in an instant? My answer to this question is that the biblical tradition is not invested in presenting God as totally powerful, totally knowing, and totally in control.

I’m not alone in this opinion. Theologian Thomas Jay Oord is one of several academic theologians who are raising objections to the simplistic doctrine that God is all-powerful. Ord’s recent book, The Death of Omnipotence and the Birth of Amipotence argues that viewing God as almighty distracts us from the ways that God’s presence is everywhere and that God patiently is restoring all things.

The God we meet in the Bible is not in total control nor does this God appear to know in advance what will happen.

The story of Noah and the Flood, reveals not a totally “in charge” creator, but a grief-struck but caring God who has been abandoned by self-destructive creatures.

We read in Genesis 5 that humanity’s malfeasance nearly undoes God’s just-completed creative work. The only remedy is meager, to put it mildly. One loyal human, Noah, under the Creator’s direction, manages to build a large boat. He rounds up breeding pairs of all the animals. The passengers on the Ark will be a capsule of a new version of creation.

The story conveys appalling loss. But in the face of this destruction Noah and God struggle together and bring about a renewal of creation. God doesn’t poof away the problem. But God is there. God cares. God pushes back chaotic waters anew. And a new start is secured.

Flip to the New Testament. The self-disempowerment of God in Jesus’ ministry gives yet more reasons to set aside omnipotence as a divine attribute.

Even Jesus’ healing miracles give a startling look at divine disempowerment. One example is the woman healed of a bleeding disorder. Mark’s narrative shows her struggling through the press of a crowd to lunge for the briefest touch of Jesus’ garment, which appears to extract some kind of healing energy from Jesus. For his part, Jesus refuses to take credit.

“Your faith,” he insists, “has made you well.” (Mark 5.25ff)

This story is no isolated incident. The paralytic at the Bethsaida Pool somehow stood up on his own at Jesus’ urging (John 5.1ff).

In one of the most often read stories in the New Testament, Jesus forgoes demonstrations of power as he is tempted in the desert. Satan tempts Jesus to don the powers of a superstar to assume his messianic calling.

The self-limitation of God is not difficult to understand logically. First, the very concept of total power carries some logical limits. Could an all-powerful God make a rock that he could not lift?

Love

Every love relationship necessarily entails one or both partners pulling back their control of the other. To the degree that God loved the creation and humans is the degree to which God allowed them to exist and do as they pleased.

In the place of total power, we see an array of relational divine attributes. God is patient and time-consuming. God is ever at hand. God is emotionally engaged and long-suffering.

Put whimsically, God exchanges control for a relationship. God’s relationship with the creation is more like parenting than policing. So, the drama of both the Bible and human history is a continual renewal of the creation versus chaos struggle.

So where is God in the current ecological catastrophe? It appears we can abandon any yearning for that single spectacular act of divine power, one that makes irrelevant the efforts of hundreds of firefighters and aircraft.

Of course, God wants the flames and smoke to stop. But he created the world and its people to be co-creators. Freely and enthusiastically created beings are designed to love and relate with God personally rather than being molded like clay in the hands of an all-controlling potter. When we are inert matter under constant management, we are simply undifferentiated parts of God himself.

Somewhere in Canada’s north woods, a team of exhausted smoke jumpers is digging a fire break trench. They’re exhausted and sweating. But they’re doing creational work. I’m guessing that the creator God works with them by inspiring them and enlarging their capacity and giving just enough to make this trench successful in halting a small part of the fire. A few trees are saved.

Multiply this image thousands of times. God also is in the public administrator’s office quietly making the decision-making more effective.

Beyond our understanding, God took a week, not a second, to create the world.

And that was before the intrusion of human malfeasance. The spectacular, all-powerful idea of God willing all things into perfect existence is not how Genesis tells us originating creation happened. We should not expect it now.

God Continues to Create

Old Testament scholars have coined the term “continuous creation.” There is also the term “new creation,” which appears in the Book of Revelation. We can take from this that the entire biblical and historical drama is a fundamentally ongoing creative activity.

Let’s go back to Genesis. The events narrated in the last few verses of the first creation story leave a superficial impression that the creation phase is closing out and that God will be doing other things, like getting Israel going and bringing Christ into the world.

The Creator’s pronouncement that his work is “very good” implies a kind of closure or conclusion (Genesis 1.31). The word “good” in the creation story really means that everything is on the right track.

It doesn’t mean that everything has reached perfection.

It doesn’t take long for the freshly created world and its people to use their autonomy to strike out in their own direction marring the goodness of God’s work.

I like to imagine a painter at her easel finishing a carefully crafted painting.

Just as the artist is putting the finishing touches on her work, someone throws a bucket of paint on the not-yet-dry picture.

Suddenly, the artist starts brushing furiously to restore her artwork.

What I find illuminating about this image of the artist is that she uses the same array of skills and techniques to restore the damaged painting as she used in crafting it in the first place. I’m imagining that her skills in color mixing, brushwork, composition, and perspective are all useful in restoring and then finishing the work.

Transfer this thought to the ideas of originating creation and continuing creation. God the Creator has brought the world to a certain good point of development. The very creative techniques that God used in the first place are redeployed in an effort not only to remediate the damage inflicted on the world by errant humans. God is still bringing order out of chaos, delegating important tasks to humans, and relying on creatures to bring forth generation after generation of descendants.

One example of continuing creation illustrates how God’s saving work is deeply creative.

After the enslaved Hebrews, with God’s help, get out of Egypt we read that the Red Sea yawned open allowing a way of escape from the Pharaoh’s chariots. Reminiscent of the primeval ordering of the watery chaos, the Hebrews slip through the divided waters. Tragically, the pursuing chariots of Egypt also charge between the divided waters as they close together.

In this case, the tamed waters preserve God’s people and the rescued Hebrews burst out in spontaneous celebration. Significantly, there’s a hint of the old creation story in the celebratory song that they sing on the opposite shore of the Red Sea:

You blew with your wind, the sea covered them;

They sank like lead in the mighty waters. Ex. 15.10

Exodus15.10

Again, to the question of God’s presence in the burning forests of Canada:

We can think of the fires as a hot version of the Genesis Flood. As with that situation, God is not entirely in control of a world spinning out of control. And like the Noah story, our context of human-caused climate change also represents the human caused (sinful) unbalancing of Creation’s original design.

And now neither humans nor natural processes like rain, are going to prevent appalling destruction.

Where is God? God is weeping and looking for righteous people who will strive with him to restore healing to the created order. Additionally, God is working closely and in countless ways to restore and perfect what otherwise portends to be a sweeping catastrophe.

We’ve stated that God is not relying on a cataclysmic overpowering miracle to set everything to rights. But in thousands of little ways, there is a renewing presence.

The Spheres of God, Humanity, and Creation Influence Each Other

Our secular outlook, which tends to strip life of spiritual significance, blocks us from seeing the non-human created order not only as within the scope of God’s love and saving intentions but also as a character in the biblical drama.

The biblical outlook presents the relationship between humanity, “nature,” and God as family-like. This means that God has a nurturing saving love for humanity. And humanity relates to God in worship and service. What we overlook are the two-way relationships between God and nature and humanity and nature.

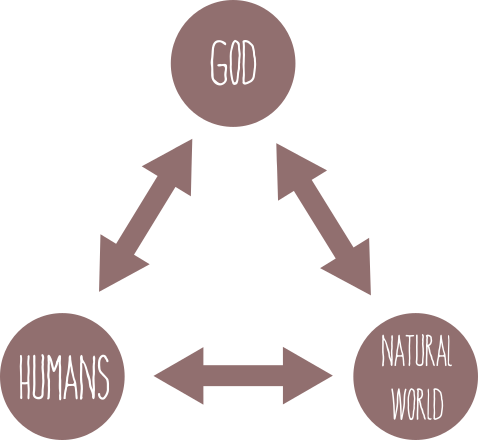

At the risk of oversimplification, I’d propose using the following diagram as an aid in thinking about the various relationships. In other words, Creation starts a love relationship The ideal is that each relationship is animated by love. God loves people and vice versa. People love God. God loves animals and non-living things. The reverse is true. People love the natural world. And vice versa. The Bible is sprinkled with evidence of all these loves.

One implication of this scheme is that a disturbance in one relationship brings disturbances in others. In the Bible, upset and destruction in the natural world are generally a consequence of problems in other relationships.

Because the idea of the created order consisting of three interlocking relationships may be both new and straightforward, I’d like to cite three Old Testament examples of these principles.

The Garden of Eden

Take the story of Adam and Eve. Their fundamental mistake was to mistrust God and God’s loving intentions.

What is tragic is that their sin leads to degradation in all the other polls of the chart above. The man and woman lose the innocence of their companionship. The man will need to struggle in farming and getting food. The companionate relationship with the snake turns to fear and distrust. God banishes/the man and woman self-banish themselves from the Eden’s pleasures and abundance.

In sum, the disturbance in the God-human relationship spreads with alarming destructiveness to the cosmic sphere, not to mention to their own children and other people.

Egypt in the Book of Exodus

We read in Exodus that Egypt suffered a series of ecological catastrophes, known as the 10 Plagues. These severely disrupted its serene and abundant life in the Nile Valley.

Consider the character of these plagues. The Nile River becomes polluted by foul bacteria. This problem brings on an exaggerated hatch of fleas and flies. Then come frogs which hop into houses and, disgustingly, into mixing bowls.

Each of the plagues is a natural occurrence that has broken out of the confines of created orderliness. Something has unbalanced Egypt’s ecosystem. Creation has lapsed into disorder.

Why is this happening? There is a recurring biblical principle that links human behavior, especially bad behavior, to the well-being of the natural world. Where human cruelty and stupidity are rampant, so is ecological disruption.

The Old Testament Prophets

This vivid passage from Jeremiah is one among many prophets that link sin and ecological disruption.

If a man divorces his wife

and she goes from him

and becomes another man’s wife,

will he return to her?

Would not such a land be greatly polluted?

You have played the whore with many lovers;

and would you return to me?

says the Lord.

2 Look up to the bare heights, and see!

Where have you not been lain with?

By the waysides, you have sat waiting for lovers,

like a nomad in the wilderness.

You have polluted the land

with your whoring and wickedness.

3 Therefore the showers have been withheld,

and the spring rain has not come;

yet you have the forehead of a whore,

you refuse to be ashamed.

4 Have you not just now called to me,

‘My Father, you are the friend of my youth—

5 will he be angry forever,

will he be indignant to the end?’

This is how you have spoken,

but you have done all the evil that you could.

—Jeremiah 3.1-5

We’re asking the question, “Where is God in this smoke” and we’re proposing another part of the answer. Specifically, we’re noticing that the ecological upset of warming, drought, fire, and smoke is related to the upset in other relationships, certainly between humanity and the world, but also between people and between people and God.

What may be startling for readers who are contemplating the interrelated character of creation is that climate and social scientists have made the same linkages. Massachusetts Institute of Technology economists Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo in their best seller, Good Economics for Hard Times are wonderfully straight-forward in their economic explanation of climate change. We have a warming planet primarily because of profligate consumption by wealthy nations, mostly the United States, and by rich citizens everywhere in the world.

Of course, it’s too simple simply to say that the wealthy are at fault as if they lit the Canadian fires personally. There are many other business practices and natural processes that feed this problem.

I’m thinking mostly of the large role farming practices and vast cattle lots play in unbalancing the Carbon Dioxide density in the atmosphere. The greenhouse effect kicks in driving the average global temperatures up and in short order water, wind, and fire are running rampant.

What I’m trying to say in this section is that the fires (and hurricanes and floods for that matter) and the conditions that led to them bear an uncanny resemblance to the disordered natural catastrophes in the Bible.

So Where Is God?

Never has humanity faced its own demise. And, as Chris Hedges points out, the death of our species is much the same as our personal deaths. In turn, the same defense mechanism that prevents us from absorbing and contemplating the ending of our personal histories is probably operating with respect to our collective deaths—our extinction.

The Bible does indeed ponder comprehensive collapse and the extremes of both human experience and the beginnings and endings of all things. This makes the scriptures and biblical faith strikingly conversant with the dire time that humanity is experiencing right now.

The forgoing citations of biblical themes are representative of the many ways that a close reading of the scriptural materials, mostly from the neglected creational texts, yield substantial insight into how the Creator and God of Judaism and Christianity cares about, interacts with, and evaluates the crisis of climate change.

Cluster of Theological Themes

In trying to lift God’s role and attitude towards the terrible fires I’ve touched on several interacting principles in the Bible, all related to the character of creation. This cluster of theological themes includes:

- The fires are not indifferent or value-free. It matters to God and all of creation that Canada’s forests are suffering, just as it matters that destructive hurricanes, floods, or warming weather are increasing in severity. These things matter because God created the world, declared it good. Additionally, God will bring all of it to newness and splendor someday.

- God is not and cannot (or will not) decree everything to be set right by an act of divine power.

- The character of creation sees God exercising creative energies in untold details, over time and in collaboration with especially people, but also animals, non-living creation, and possibly other spirit beings.

- The world of the Bible envisions a relationship between justice and peace in human society and peaceableness and order in the non-human living and non-living created sphere.

- Animals and nature are actors in the biblical drama, they are within the sphere of redemption, and they serve God by praising God and showing truth.

One Reply to “Where Is God in This Smoke?”

This is a an awesome , thoughtful, stimulating piece. I will continue to savor it and could ponder and discuss it for hours on end. It brings out and opens Biblical concepts and elements that I have read for years but have never seen before! Thanks for and eye opening and stimulating work Doug!