The Color of Law

Richard Rothstein’s The Color of Law has convinced me that the segregated character of American cities is the government’s fault. Of course, individual racism has had a role. Back in the 1970s, a small-minded neighbor of mine tried to rally friends to purchase a house on his street in order to prevent immigrants from moving in. Than kind of local animosity has contributed to segregating America. But what Rothstein has done is to demonstrate that segregating America’s housing has been more or less a governmental project throughout the 20th century. This effort reached its zenith during and after the Second World War. And the results are still very much with us.

The two world wars brought a need for war manufacturing and an ample workforce. Workers flooded into temporary living quarters around production centers like the shipyards in Richmond, California. This rush to step up production opened the door for government bureaucrats to assign Whites to some neighborhoods and Blacks to others. Not surprisingly, Blacks ended up in inferior structures sometimes miles away from plants and yards.

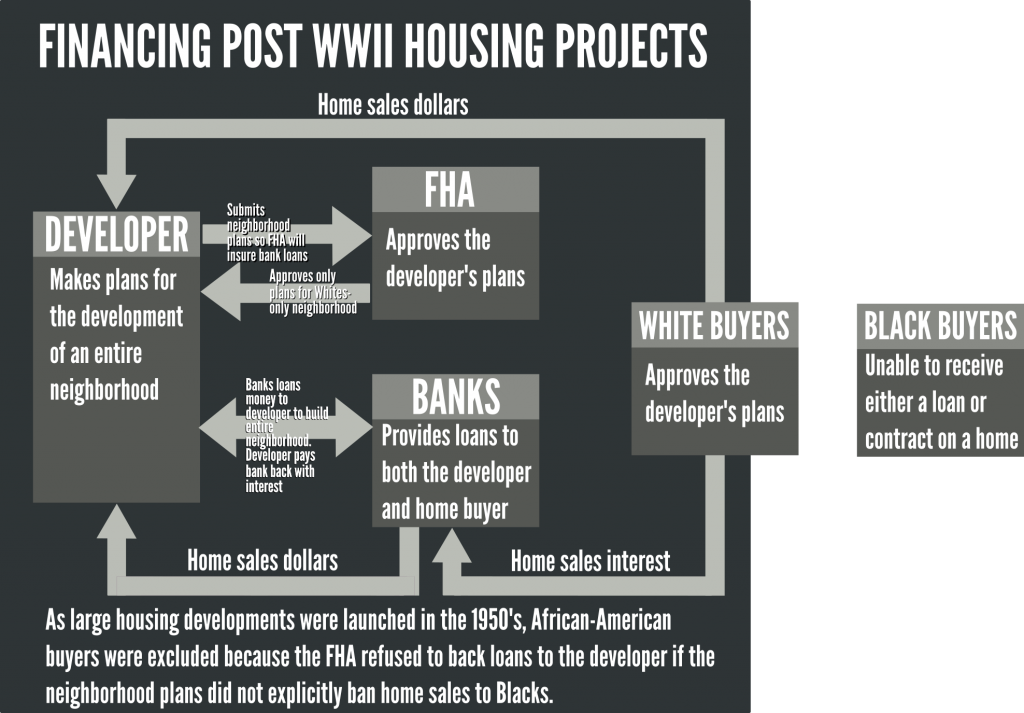

The pattern of government influence over housing continued after the wars. In the late 1940s, in order to accommodate returning GIs, the Veterans Administration and Federal Housing Administration worked with banks and builders to create a post-war housing boom. The Levittown projects in Pennsylvania and New Jersey were typical of an exuburant vision of American life and prosperity. Many of the large planned neighborhoods simply continued the segregation of Blacks and Whites. Explicit FHA directives tied neighborhood developers to Whites-only policies as a condition for receiving loan guarantees necessary for construction and mortgages.

As the country moved away from Jim Crow and school segregation at the beginning of the Civil Rights era, housing continued sort buyers by race. Many of the methods of discouraging mixed race neighborhoods were more devious means than written policies. Highway projects for example had a tendency to run through Black neighborhoods, displacing thousands of homeowners. Additionally, local police were known to simply stand by as mobs of neighbors showed up to harass Black homebuyers. Obviously, municipalities didn’t have much of a moral investment in protecting the rights of Blacks to live where they pleased. It would not be an overstatement to say that driving African Americans away was more or less official policy.

Rothstein has unearthed such a devastating trove of evidence implicating the government in perpetuating Jim Crow practices that no serious reader could chalk up the segregated character of American housing to racist individuals or to some Black yearning to live separately from Whites.

Rothstein gives more in Color of Law than a look at government fingerprints all over our segregated landscape. He offers several ways to remediate the problem in his twelfth chapter, “Considering Fixes.” Most of these strategies have to do with shoring up Section 8 housing vouchers and expanding tax-advantaged building programs.

Recommendations

As I read the twelfth chapter I jotted down 15 suggestions, explicit and implied for improving the division of America’s housing into neighborhoods for Blacks and neighborhoods for Whites.

- Keep economic vitality and full employment.

- Recognize the de jure character of segregation in America.

- Teach an accurate history in middle and high school so students can have a realistic understanding of how we have come to be in the mess we’re in.

- Focus relentlessly on the government itself as the entity that has segregated our cities.

- Buy homes in areas like Levittown at current prices and resell them to African Americans for today’s price version of what they would pay for them if they were allowed to buy into the original Levittown. This would restore the appreciation in value.

- Provide African Americans with federal subsidies to purchase homes in formerly Whites-only suburbs.

- Ban exclusionary zoning ordinances.

- Congress could deny mortgage interest deduction to property owners in suburbs that are not taking steps to attract low and moderate-income housing.

- Through legislation, adjust zoning regulations in areas that are exclusively White to build multi-family and low or middle income units.

- Have inclusionary zoning widespread enough so that developers can’t simply move to the next town and build an exclusive suburb.

- Enable use of section 8 vouchers to provide an increased subsidy to families that rent in nonsegregated communities. Counseling and support for former public housing residents would help them adapt to living in middle class areas.

- Disallow landlords to reject Section 8 vouchers.

- Appropriate enough money so that everyone who qualifies and desires a Section 8 voucher may get one.

- Give a property tax reduction to landlords who rent to voucher holders.

- Nudge developers to build Low-income Housing Tax Credits to developers building in integrated, neighborhoods.

My Interracial Book Club

I read Color of Law as one of the books on the reading list of the Manasota Interracial Book Club, where I’ve been a member since 2017. Month after month about 10 of us gather to discuss a substantial book about Black history and racial justice. At the end of the first year I felt that I’d gotten sufficiently acquainted with the Black experience. I thought that the book club would break up and I would move on to other subjects.

But we continued. And I continued. I was naïve to assume that I had covered Black History’s high points or understood what it means to be black in America today. Now in my fourth year of focused reading, I continue to be surprised at how little I understand. Month after month the books and discussion pull back another veil to reveal yet something new and shocking that I’d somehow missed.

The impact of Ed Baptist’s The Half Hasn’t Been Told is still with me. We we ploughed through that tome back in 1917. It’s a long read about slavery in America. After working through that book, I realized that slavery is a much bigger and more damaging economic practice than I had realized. It has cut a deep gash on our culture that is still swollen and oozing toxins. It’s amazing the country was able to get rid of it. And in some senses hasn’t fully left it behind. That book adjusted my attitude towards my country.

Then came Isabel Wilkerson’s Warmth of Other Suns; Bryan Stevenson’s Just Mercy; and Carol Anderson’s White Rage. Month after month brings a fresh revelation. Racial animosity isn’t an unfortunate detail in American life, like litter along the interstate. Race is essential to American life.

It’s a cleansing awakening to discover in my late 60’s that I haven’t really understood my own culture; that I’ve fallen for a sanitized, Disney-like version of American life. Surprisingly, the African Americans in my reading group say much the same thing.

The Color of Law isn’t a page-turner. How could old neighborhood covenants and the nuances of Supreme Court rulings be scintillating reading? But when Rothstein is done with his readers, they realize that the ugly vista of a segregated nationwide cityscape is stamped with a US government seal. And with that bifurcated living arrangement are two terrible side effects: First, African Americans today simply do not possess the wealth that Whites do and second, Black children are locked in inferior schools. Housing disparity drives both of these persistent problems.

And Richard Rothstein has performed a real service in putting together the evidence which helps me understand exactly why Blacks continue on in their one-down status in this country.

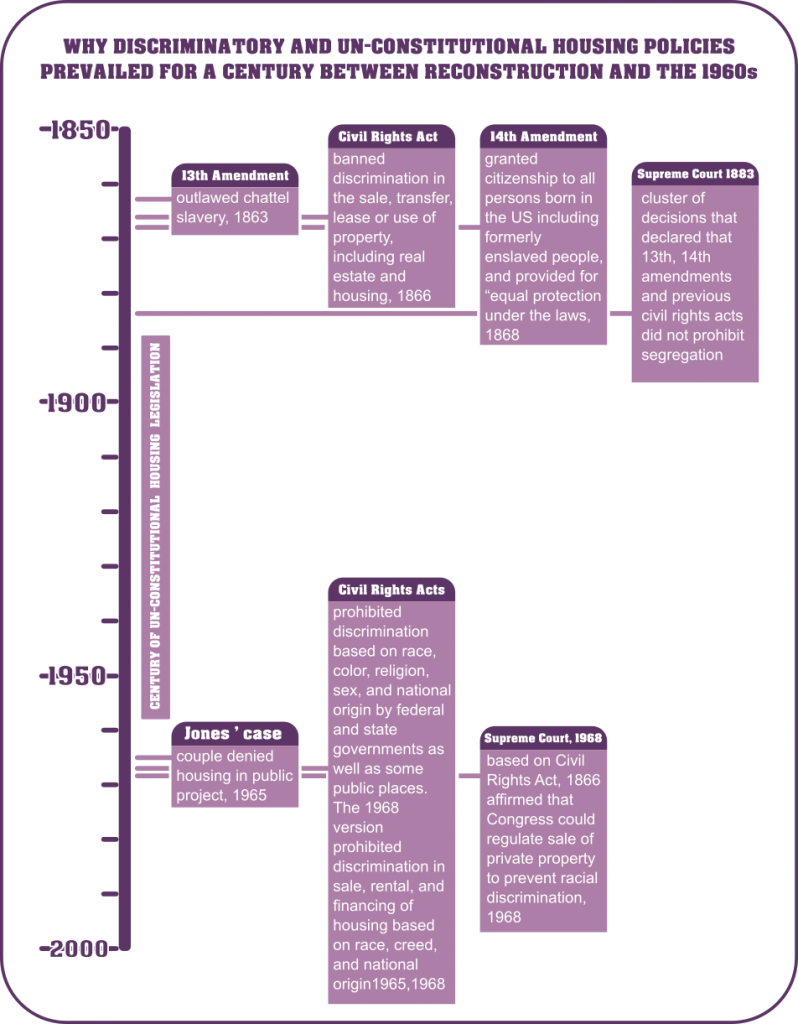

I’ve organized a simple timeline below which places several of the examples which Rothstein cites in chronological order.