“Just Mercy:” A Searing Story of Cruelty and Grace

Last night, I saw and was moved by “Just Mercy” the movie version of Bryan Stevenson’s 2014 best seller by same name. The story is about Stevenson’s efforts, early in his legal career, to overturn death penalty convictions in Alabama.

Though he is a Harvard Law grad, Stevenson opts out of a high-paid lawyer’s career in order to travel alone to Alabama. There, working out of the home of a supporter, he begins to seek appeals in the cases of death row inmates. Bit by bit, Stevenson launches an organization, The Equal Justice Initiative, which seems like a hopelessly insignificant challenger to the ruthless and racist Alabama justice system.

The book tells the tales of several death row inmates, some of whom Stevenson manages to rescue from Alabama’s electric chair.

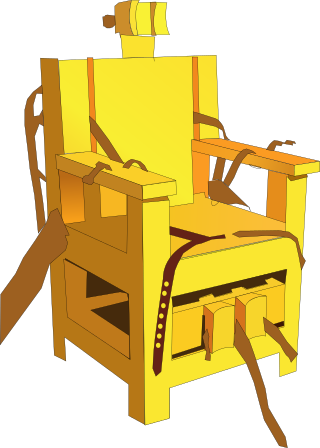

The movie version focuses on two cases One case is that of Jimmy Dill, a PTSD disabled Viet Nam Vet who foolishly sets off a bomb, killing a girl. Stevenson is unable to keep Dill from Alabama’s electric chair. Dill’s final minutes, as he is shaved and strapped into Alabama’s electric, are as harrowing as any I’ve seen on film.

The much more famous second case is that of Walter McMillian, who was framed as the murderer of Ronda Morrison a worker in a Laundromat. Walter McMillian’s tale is full of twists and turns which leave the movie-goer breathless. In the end, thanks to nationwide publicity by 60 Minutes news magazine, Walter wins a full acquittal.

The movie is a worthy representation of the book. Naturally, the film lacks the nauance or depth of the book. Nevertheless, the movie adds to the book in small ways. The Ralph Myers character, played by Tim Blake Nelson, is as vivid a representation of a flawed and broken human being as one could imagine.

Both book and movie make stunning statements both about capital punishment and race in America. Stevenson exercises amazing and perhaps even unnecessary restraint in pressing some of his strong points.

For example, Walter McMillian’s arrest for the crime is a total contrivance. He has no prior record, does not know the victim, is miles away at the time of the crime, and is in the company of dozens of friends at a large get-together at his home.

Why Walter? He is as unlikely a suspect as anyone in Monroe County. Why is his arrest and conviction put into motion? The only plausible reason is because he has just concluded a brief romantic affair with a White woman. In the Jim Crow South contact between Black men and White women was too frequently met by mob violence. To put it bluntly, Walter McMillian’s imprisonment and impending execution is a lynching. Stevenson makes very little of this leaving it to the reader to make this connection.

Just Mercy bristles with grace. The themes of sin, redemption, contrition, spiritual vocation, and reconciliation fill the book, yet Stevenson never draws any explicit linkages between his powerful experiences and Christian faith.

By playing in theaters during the Trump impeachment trial in the Senate, “Just Mercy” gives movie-goers a refreshing portrait of understated moral excellence that stands against the tide of shabbiness and mendacity gushing from Washington.

Finally, while the movie is an excellent story that traces Walter McMillan’s saga, there is a wealth of details, much of it emotionally moving, that cannot appear in a 2 hour film.

One incident near the book’s end illustrates. After Walter McMillian is exonerated and released, Stevenson takes a speaking tour in Sweden. Among his activities is to speak to an auditorium full of Swedish senior high students. Bryan Stevenson steps into the elegant auditorium:

The students listen raptly for nearly an hour as Stevenson talks about what he does as an advocate for death row inmates. When the speech ends, the students erupt into enthusiastic applause. An emotional wave engulfs the room.

The headmaster proposes that choir members in the audience sing their gratitude to Bryan. Stevenson describes the moment this way. The students lift their voices in…

Later, in his hotel room, Stevenson turns on his television to discover that Walter McMillan is giving an interview to a news team back in Alabama amid the wreckage of abandoned vehicles on his property. Stevenson sees through the television feed that Walter is a broken man

He looked soberly at the camera.

The juxtaposition of Bryan being serenaded by students with Walter, who has lost everything through his ordeal on death row, encapsulates the cruelty of the death penalty as it is administered in the United States.

Just Mercy is filled with many more shattering and grace-filled stories. The movie carries much of that into the theater, certainly enough to certify that Bryan Stevenson is a rare leader and that his book is a transforming read.

The Book: Summary and Notes

Summary of the Introduction: “Higher Ground”

Just Mercy’s introduction traces the author’s personal journey as a law student—with little commitment to his legal vocation to a seasoned defense lawyer who has spent his career in close proximity to the poor, youthful, and female people who have been systematically diminished by the American criminal justice system. Stevenson’s overarching conclusion is that the justice system degrades the humanity of those caught in its snare. He sees the justice system’s mistreatment of the poor, women, and children as a barometer, which reveals a troubling element in American society.

p. 3: Bryan Stevenson, like Debby Irving, was born in 1960. Jackson, Georgia is the site of the author’s first visit to a maximum security death row. It’s located between Atlanta and Macon.

p. 4: Author tells about his educational background. Undergraduate degree in philosophy.

p. 4: He reflects about being disoriented as a law student at Harvard. Professors used Socratic questioning. Traditional academic environment. Stevenson finished a dual degree with the Kennedy school. He also found the second degree program to be a little arid.

p. 5: He took a class from Betsy Bartholet on race and poverty litigation. This class entailed much off-campus work. He ended up working with the Southern Prisoner’s Defense Fund in Atlanta. Steve Bright was also an influencial mentor with the Southern Prisoner’s Defense Fund, Atlanta. (SPDC).

p. 6: Bright explained to the author the death penalty in compelling and memorable terms.

p.7: Impoverished people in America are executed without counsel.

Excursis: What about plugging into a system like SPDC through fund-raising as a way to get ordinary, non-lawyer, people engaged in fighting the death penalty.

p.7: Resumption of the story of meeting with Henry, the condemned man. This conversation marked a turning point in Stevenson’s vocation.

Excursis: Once again I’m reminded that Americans are losing their sense of the spirit of their own constitution.

p. 13: Stevenson ends his three hour conversation with Henry convinced that misjudgment of people is rampant in America and in our justice system.

Excursis: As it turns out, judgment and the imperative not to judge is an important Biblical Theme:

p. 13: Judging is a pervasive theme in Jesus’ teachings.

p. 13: “Racialized hierarchy…coastal Virginia, Maryland, S. Delaware. Stevenson sees prevalence of symbols (Confederate flags, statues, etc.) as reinforcing White Supremacy.

p. 14: This book is about mass incarceration and extreme punishment in America.

p. 15: One in every three Black males in the justice system. Stevenson gives here some general stats on mass incarceration.

p. 17: One of the qualities of a God-pleasing society, as laid out in Exodus, is the institution of a court system. The giving of the Law establishes the basis of a justice system. Moses, at first, is the sole judge and interpreter of the new Law. Jethro, his father-in-law encourages Moses to appoint from among the now-free Hebrew people “able persons” to administer a justice system.

p. 17: When we accuse and condemn irresponsibly we traumatize whole families, communities, and even the victims of crime. Stevenson’s list of criminal justice issues:

1. Unreliable verdicts and imprisonments of the wrong people.

2. Abused and neglected children who end up abused in adult prisons.

3. Women, whose prison presence has increased 640% in recent decades.

4. Hysteria about drugs

5. Prosecution of poor women “when pregnancy goes wrongly.”

6. People willnesses who land in prison.

7. Criminals who struggle to find redemption.

p. 17: “Each of us is more than the worst thing we’ve ever done.” “The opposite of poverty is not wealth…it’s justice.” We are all implicated when we allow other people to be mistreated.

Chapter 1: “Mockingbird Players”

This chapter explores how anti-miscegenation laws and attitudes were, until recently, a strong influence on Southern law enforcement. The chapter traces Afro-American William McMillian’s fall from social legitimacy because of an extra-marital affair with a White woman. While he committed no crime the affair in Alabama made him an easy scapegoat for a police department that needed to make an arrest due to public pressure.

p.21: Stevenson begins by telling of a Judge Key of Alabama who tries to dissuade Stevenson from defending Walter McMillian. Alabama, mid-1980’s, had no public defender at all…w. 100 death row inmates. Stevenson even tries to start a non-profit to provide legal representation for capital crime convicts.

p. 23: William McMillian came from Monroe County, Alabama where Harper Lee lived. The town has attempted to cash in on her novel’s success.

p.24: Education for Blacks in rural Alabama in 1950’s was slim.

p. 25: Walter McMillian avoided Alabama’s collapse of cotton growing by getting into the pulp and saw mill business. Walter’s business independence was resented by local Whites.

p. 28: In 1880’s in Alabama a Tony Pace and Mary Cox, a Black man and White woman respectively, fell in love. They were arrested and convicted and represented by progressive lawyer John Tompkins. The Supreme Court upheld Alabama’s restrictions on interracial sex.

p. 29: The US Supreme Court in 1967 struck down anti-miscegenation laws in case named Loving v. Virginia. Anti-miscegenation law still existed in 1986.

p. 30: Ronda Morrison, teen, found shot 3 times in Monroe Cleaners. No suspects. Two Latino men were suspected, but cleared, as were two others.

p.31 Karen Kelly took up w/ criminal scar-faced character, began dealing drugs, and was implicated in Vickie Pittman’s murder. In confusion Walter McMillian became suspect.

Chapter 1: “Mockingbird Players” Summary

This chapter explores how anti-miscegenation laws and attitudes were, until recently, a strong influence on Southern law enforcement. The chapter traces Afro-American William McMillian’s fall from social legitimacy because of an extra-marital affair with a White woman. While he committed no crime the affair in Alabama made him an easy scapegoat for a police department that needed to make an arrest due to public pressure.

Chapter 2: “Stand”

p.35: Discusses apartment-sharing with Steve Bright and the shared apartment with Charlie Bliss.

p.36: Author describes representing death row inmates in Alabama and working to start a similar project in Atlanta.

p.36: Prison conditions poor in 1970’s which were exposed through media coverage of Attica Prison riots. The growing prison population made poor living conditions worse. This sometimes led to the death of prisoners.

p. 37: Start of description of Ruffin case in Gadsden, Al. He was stopped for traffic violations, beaten by police.

p. 38: Story of teen boy shot by police in his car. Civil rights leaders persuaded Stevenson to investigate. Stevenson was already very busy with death penalty cases.

p.39: Stevenson himself was confronted by Atlanta police, dressed in military garb. After handcuffing and searching car, they drove off.

p. 42: Stevenson wondered about other Black men and boys who would not know how to deal with the police. He filed lengthy complaint with the Atlanta Police.

p. 43: In realizing how unprepared, as a lawyer, he was to deal with police, he continued to worry about other Black men.

p.44: The chapter returns to the Ruffin case in Gadsden, which was resolved. Stevenson resolves to speak with kids personally in church youth groups and community organizations.

Excursus: Stevenson reflects here on the fact that he was a lawyer being the element that gave him believability in making his complaint with the Atlanta police. The whole incident underscores the lack of clout poor Blacks have when their rights are abused.

p.45: Moving description of encounter in Alabama with wheelchair-bound man who had been beaten over the years in his attempts to stand up for justice.

Excursus: It’s important to remember that Jesus Christ takes up the into his being the condition of being denied justice. He was wrongfully arrested, tried, incarcerated, and executed. Jesus’ trip to Jerusalem and his death at the hands of conspiring elites, exposes humanity’s hatred and attack of God himself. If God becomes weak and vulnerable, then his sinning, covenant-breaking creatures will murder him—through the “justice” system.

Chapter 2 “Stand” Summary

The encounter of Black men and boys with Police in America, especially in the South, confronts them with numerous dangers that they are ill-prepared to handle, especially if they are not informed on how to handle themselves. Stevenson himself describes his own encounter with the Atlanta police, which could have resulted in his death had he not been a lawyer.

Chapter 3: “Trials and Tribulation”

p.47: The narrative returns to Walter McMillian who was eventually arrested by a local sheriff who was fending off an impatient public which was criticizing their law enforcement. At length, McMillian was arrested on a charge that he had sexually assaulted

p. 48: The lynching of Michael Donald in Mobile, an arbitrary victim of public rage, following the courts failure to charge another Black man. Arresting officer, referencing, Donald’s lynching, threatened McMillian with the same violence. After questioning McMillian. In turn the police locked him up.

p.51: Walter McMillian was at home fixing transmission when Ronda Morrison was murdered. The group at McMillian’s home heard about the 10:15 a.m. murder. Walter’s presence at his own home received attestation even on the police log of an officer who stopped to eat at McMillian’s home.

p. 52: Both Myers and McMillian were placed on death row before their trials.

p.55: At Holman Prison where executions had resumed after several year’s moratorium, McMillian entered a community completely pre-occupied with the electric chair in their midst.

Excursus: I wonder why, after periodic suspensions of the death penalty, it has periodically recovered support. In 2018, support increased from 49% to 54% of Americans.

p.55: McMillian naively believed that his alibi would win his release.

p.56: Sheriff Tate was angered that McMillian would hire an outside lawyer.

p.58: Myers, unhinged by the death row experience, phoned Sheriff Tate and agreed to say anything to get off of death row.

p.58: Blacks in Alabama only began to exercise right to vote in 1970. Whatever, the case, the act of voting by Blacks invariably draws out efforts at voter suppression.

Ted Pearson, District Attorney, wanted to end his career on a high note with the conviction of Walter McMillian.

p.59: Alabama had a long history of manipulating juries so that they were exclusively Black. Courts found their way around a 1970’s law which declared all-white juries unconstitutional.

p.59: A “peremptory strike” in jury selection is where each lawyer may dismiss a jurist without giving a reason. This process often leads to all White juries. This practice still happens.

p.60: Walter McMillian heard from fellow death row prisoners some stunning tales of cases with all-White juries.

p.61: The new Batson Decision was a Supreme Court ruling in 1986 that lawyers could not dismiss jurors without explanation in order to eliminate Blacks from juries. Additionally, in Alabama, requesting a change of venue was a futile act.

Walter’s lawyers, Chestnut and Boynton had little hope that their pre-trial motions would be granted. Cynically the DA and judge agreed to change to a low-Black population county, Baldwin County, Alabama.

p.63: Ralph Myers again decided he didn’t want to testify against Walter McMillian and implicate himself in the process in a crime he didn’t commit. In response, officials put him back on death row, got him a psych evaluation, and convinced him of futility of his situation. He capitulated and agreed to testify.

p.65: Walter was convicted by nearly all-White jury. Ralph testified against him claiming that Walter had forced him to drive to the cleaners where th murder took place. Ralph’s testimony was clearly bizarre

p.66: Bill Hooks (Jailhouse snitch) testified to seeing Walter’s truck at cleaners; Joe Hightower repeated this lie, all under oath.

After perfunctory trial, jury found Walter guilty.

Chapter 3, “Trials and Tribulation” Summary

This chapter chronicles Walter McMillian’s experience in custody leading up to his trial and conviction. This case underscores several procedural injustices that enable a White law enforcement, court and prison system to manufacture convictions of innocent Blacks even when a jury trial is conducted. The author expands on false testimony by socially defunct people, public pressure of the sheriff’s office to hurry to an arrest, housing suspects on death row even before trial, peremptory strike, which dismisses potential Black jurors without giving reason, and denying change of venue motions.

Chapter 4: “The Old Rugged Cross”

p.67: In 1989, author and Ava Ansley opened their non-profit law center to provide legal services to death row inmates.

p.68: The venture quickly collapsed, forcing a reboot in a Montgomery location. They had to raise their own funds.

In 1989, there was a new push for executions after 13 year hiatus.

Inmates urged Stevenson to pay attention to Michael Lindsey and Horace Dunkins whose executions were approaching.

p.69: Michael Lindsey’s judge overrode the jury’s life imprisonment decision and consigned Lindsey to execution.

p.70: Author expands on practice of judge overrides, which is when judges bump up penalties from life in prison to death penalty. These are often politically motivated to attract votes from a public that tends to like tough on crime judges.

p.71: Michael Lindsey was electrocuted in 1989. Lawyers, confronted with a Supreme Court decision upholding judge overrides, had no constitutional grounds to appeal Lindsey’s punishment.

Dunkin’s execution was botched. This led to an autopsy, which the family wanted to avoid for religious reasons.

p.72: With volunteer lawyer, Dunkins’ parents sued.

Excursus: One of Stevenson’s sub-themes is the lack of financial resources to challenge the death penalty and its victims.

Herbert Richardson frantically phoned Stevenson shortly after his execution date, three weeks hence, was set.

p.73: Trying to get stay of execution is a more than full-time job.

Excursus: Stevenson’s description of Richardson’s pleas for him to take on his case reminds me of Jesus’ description of the imploring woman pleading with the could-care-less judge. Prayer which changes things looks like Richardson’s begging.

p.74: Richardson’s background. As a Vietnam vet he suffered a “complete mental breakdown.” Later, he had a romantic relationship with a nurse who had helped him. When she tried to break off relationship, Herbert concocted a far-fetched plan to plant a bomb, detonate it, and then run to save his frightened nurse-friend. The bomb, however, ends up killing child.

p.77: Alabama decided to invoke “transferred intent” to make Herbert’s crime eligible for death penalty. Volunteer lawyer spent little time on case and the judge condemned Herbert to death.

p.81: After an unsuccessful appeal for a stay of execution by having an explosives expert testify, Stevenson encounters the murdered child’s mother and siblings. They disclose that they’d never been compensated for trauma related to the bomb incident.

Excursus: Stevenson’s weariness reminds me of the “Whisky Priest” who was completely exhausted and stalked by authorities. Nevertheless, he managed to minister to desperate people and even celebrates Mas. From Graham Green’s, The Power and the Glory.

p.82: Curious that family of victims asked Stevenson for help despite the fact that he is counsel for the killer of their child.

p.85: Stevenson describes failure of his last appeal, the two hour drive to Holman Prison, and meeting with Herbert during his final hour with his family.

p.87: Unexpectedly, Herbert’s family becomes inconsolable and clingy. Officials have difficulty removing the condemned man for his execution.

Chapter 4: “The Old Rugged Cross” Summary

This chapter traces Herbert Richardson’s case from his bizarre crime, which accidentally killed a child to his death in Alabama’s electric chair. A crucial twist that led to the tragic scene of Richardson’s family weeping for him in the hour before his execution, was the “judge override” which switched his life imprisonment jury verdict to execution. A secondary theme in this chapter is the role of incompetent lawyers in leaving the accused without competent representation.

Chapter 5: “Of the Coming of John”

p.92: Stevenson visited with Walter McMillian’s wife and daughter after Walter’s trial. The house was dilapidated. Stevenson was nevertheless treated well by Walter’s family.

p.97: The visit with Minnie, Walter’s wife, continues after she and Stevenson drive to a remote community. There they find a gathering of Walter’s friends and family.

p.99: Stevenson discusses the appeals process with the extended family. The family is gracious and encouraging to Stevenson. Despite the warm reception by Walter’s support community, it’s clear that they have been convulsed by the injustice that has been focused on Walter.

p. 100: The book’s author summarizes the short story, “The Coming of John,” which appeared in Dubois, The Souls of Black Folk.

p. 101: Stevenson reflects on the impact of injustice on an entire community. The spreading ripples of trauma are especially destructive when the jailed person is a community leader.

Excursus: The original disciple group labored under similar trauma when Jesus was executed. This trauma was overcome in many ways by Jesus’ return from the grave and the dramatic empowerment of the Holy Spirit’s arrival. The points of comparison between Jesus’ trial and death and the stories in Just Mercy are more than incidental. Jesus takes on in his earthly ministry the life circumstances of hard-living people suggesting that the good news has a special audience in those who are captive and condemned.

p. 103: Sam Crook, a White man for whom Walter had worked, phoned Stevenson to declare that he knew that Walter was innocent. He also knew the names and the plot to have Walter arrested and convicted. Crook pledges his support of Stevenson’s efforts.

p. 104: Stevenson discusses the importance for attorney-client familiarity. When lawyers go to the trouble of creating a friendship with the condemned client, they may uncover details in the condemn’s life situation that reduce the degree of cruelty or cold-bloodedness of the crime. Friendships make the argument for extenuating circumstances more compelling.

Excursus: Stevenson insists that multiple, time-consuming visits with the condemned are crucial for the development of the defense’s argument. This reminds me of the Liberation Theologian’s idea of “accompaniment.” Friendship with a struggling person is a form of pastoral care.

p.104: Here begins a new theme. Darnell Houston phones Stevenson, saying that he can prove Walter’s innocence.

p. 105: Bill Hooks had been in the Monroe County Jail on burglary charges. Law Enforcement or court officials promised him release if he cold link Walter McMillian’s truck to the Morrison murder. Darnell Houston was working with Bill Hooks at an auto parts store when the Morrison murder took place. Hooks never left work.

p. 107: Monroe County’s District Attorney. Before becoming DA, Chapman represented Karen Kelly, the waitress and Walter’s married lover. Additionally, Darnell Houston was arrested shortly after contacting Stevenson about Bill Hooks.

Excursus: Stevenson returns to the irony of Monroe county’s fame as the setting of To Kill a Mockingbird. The community basks in their reputation of being Harper Lee’s inspiration, but continues to inflict blatant racial injustice on its Black citizens.

p.110: The new Monroe Co. DA, Tom Chapman, is convinced of the rightness of Walter’s conviction.

p. 112: Alabama law requires that the testimony of an accomplice to a crime, namely Ralph Myers the driver, be confirmed by a second witness, namely by Bill Hooks, Myer’s co-worker. Darnell Houston is saying that Hooks is lying. Stevenson presents this revelation to Tom Chapman.

p. 112: Stevenson visits Darnell Houston.

p. 113: Stevenson is painting a picture of a Southern justice system, which entails police and courts, that does whatever it pleases unhindered by accountability.

Chapter 5: “The Coming of John” Summary

This chapter explores how a capital punishment conviction has impact on an entire community. Additionally, it explores how lawyers develop an appeal case after the initial trial and judgment. Stevenson follows three threads: 1) the impact on the convicted’s family, which in Walter’s case is dispirited yet hopeful. 2) The development of the appeal, which sometimes uncovers vast amounts of information that was suppressed or overlooked during the original trial. The phone calls from Sam Crook and Darnell Houston provide evidence for Walter’s innocence. 3) The counter-attack by the justice system on any causes that might re-open or overturn what they want to be a closed case.

Chapter 6: “Surely Doomed”

p. 115: The US and Japan are the only developed countries that still have capital punishment. Only a handful of countries permit the death penalty for minors. The United States is among them. Since 1990, the following countries have executed people who committed their crimes as juvenals: China, Bangladesh, Congo, Iran, Iraq, Japan, Nigeria, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Yemen, and the United States.

p. 115: Alabama has more juveniles on death row than any other state or country in the world.

p. 116: Stevenson agrees to visit Charlie, a youth who committed a crime when he was 14. Initially, Stevenson doesn’t want to take Charlie’s case. He does read report, which details Charlie’s shooting of a man named George.

p. 117: George beat his girlfriend, Charlie’s mother. On one occasion George punches and knocks out Charlie’s mother.

p. 120: Charlie ends up shooting the drunken George, who turns out to be a police officer. Not surprisingly the prosecutor in the case insisted that Charlie be fried as an adult.

On his first visit with Charlie, Stevenson is shocked at how young the boy looks. He also has difficulty getting Charlie to respond to questions or open himself for help.

p. 123: Charlie indicates that he has been sexually abused while in custody.

p. 124: Whereupon Stevenson visits the judge, gets the child moved to a protected cell, and petitions for a juvenile, rather than adult, trial.

p. 125: Later, following a talk with a church group, Stevenson is approached by a couple who wish to assist Charlie. The couple, the Jennings, were simple retired people who loved children.

p. 126: The Jennings helped Charlie get his high school equivalency and financed his college.

Chapter 6 “Surely Doomed” Summary

This chapter revolves around Charlie, who at 14, shot his mother’s abusive boyfriend, George. The crime took place after George had knocked Charlie’s mother unconscious. Charlie is one sad example of America’s child incarceration practice, which often begins by charging juvinele offenders as adults and confining them in adult jails or prisons. The chapter ends happily with Charlie’s release to the juvenial system thanks to Stevenson’s intervention. At length, Charlie is freed entirely and, thanks to the Jennings, has a place to grow up and the financial means to attend college.

Chapter 7: “Justice Denied”

p. 127: Stevenson’s petition for a reduction in Walter’s sentence is denied.

p. 128: Alabama’s Judicial Building in Montgomery is situated in the midst of several iconic sites associated with the Civil Rights Movement. Stevenson mentions the Dexter Ave. Baptist, Governor Patterson, Geo Wallace, the Freedom Riders. These memorials to racial justice, ironically, have no power to secure a fair trial for Walter McMillian.

p. 129: Stevenson regrets that he didn’t push the McMillian Family to be present during the appeal hearing. The appeals process could follow one of several possible paths, including appeal to the State Supreme Court.

p. 130: It’s at this point that Michael O’Connor, a former heroin addict and Yale Law School graduate, is brought as a team member in Stevenson’s law office.

p. 131: After working with Michael on Walter’s case, Stevenson decides that they’d probably need to solve the Morrison murder on their own in order to secure Walter’s release. Additionally, Sheriff Tate has been paying Bill Hooks and rewarding him with release from confinement in exchange for his testimony against McMillian. The lawyers continue to find overlooked exculpatory evidence.

p. 133: In an unforeseen phone call, Ralph Myers tells Stevenson he wants to recant his story. This shift in position comes after Myer’s therapy group encourages him to rectify the situation that his lying has created for Walter.

p. 136: Myers is Vicki Pittman’s killer.

p. 141: The author, Stevenson, discusses the Victim Impact Movement, which is a tangible outgrowth of the trend towards the “individualization of victimhood.”

p. 144: The bad news drought suddenly ends with a cloud burst of good news. The Alabama Supreme Court grants Stevenson’s appeal for a stay for Walter. This ruling signals the high court’s tacit agreement that something is amiss in Walter’s case. Also, the stay opens to Stevenson and O’Connor the file drawers in the police station and courts. A flood of new evidence comes into Stevenson’s hands.

p. 145: In the meeting between the police and Stevenson and O’Connor, Sheriff Tate wonders aloud whether the defense attorneys are getting paid for their work.

p. 146: As Walter’s attorneys comb through their newly acquired evidence some police officer’s names surface as possible participants or conspirators in the Pittman murder. Following protocol, Stevenson notifies the FBI.

Stevenson and O’Connor visit Mozelle and Onzelle, Vicki Pittman’s aunts. These two colorful women want to solve their niece’s murder. Their brother, Vic Pittman, is a shady character. The sisters’ information and insights were dismissed as insignificant prattle of poor White trash.

The author launches on a lengthy parenthesis about the victim rights movement which individualized crime victims. This is a philosophical departure from the legal tradition that sees an entire community as the victim.

Chapter 7 “Justice Denied” Summary

This chapter relates several interrelated developments that followed the initial denial of Walter’s appeal. These include the hiring of a new attorney, Michael O’Connor, Ralph Myer’s withdrawal of his former testimony that he was an accessory to the Morrison murder, an interview with Walter’s lover and inmate, Karen Kelly, the conversation with Onzelle and Mozelle, Vicki Pittman’s aunts, and most importantly, the Alabama Supreme Court stay of execution. The chapter is sprinkled with Stevenson’s criticism of the Victim Right’s Movement.

Chapter 8: “All God’s Children”

p. 149: The chapter begins with Trina’s story. Trina is one of 12 children who was brutally abused by her father. Later Trina starts a house fire which results in the death of two boys.

p. 150: Poorly represented, Trina stands trial as an adult for 2nd degree murder and receives a mandatory life imprisonment sentence.

p. 151: Raped in prison, Trina is forced to give birth handcuffed to a bed. Trina will likely die in prison because she is one of 500 people in Pennsylvania who, with mandatory sentencing restrictions, have received life sentences.

p. 152: Ian Manuel robs a Tampa couple and in the process shoots Debbie Baigre, a crime which lands him in prison for life. Seeing Ian’s small stature, prison guards shield him from prison sexual abuse by placing him in solitary confinement. Under the stress of unending solitude, Ian attempts suicide and cuts himself.

p. 153: Several years into his confinement, Ian impulsively uses his once a month phone allowance to dial Debbie Baigre, his victim. Into the receiver, Ian pours out an emotional apology. Baigre is moved and petitions a judge insisting that Ian’s sentence is too harsh.

Florida, Stevenson observes, has the world’s largest population of inmates who committed crimes as children and are condemned to life in prison.

p. 153: Antonio Nunez lives in violent south Los Angeles and is abused by his father.

p. 154: Antonio is shot while riding his bicycle. His brother, attempting to help Antonio, is also shot and killed.

p. 155: Stuck in the prison system and on probation, Antonio returns to LA from Las Vegas. Traumatized to be back in South Central LA, Antonio gets a gun for self-defense and promptly ends up in custody.

p. 156: Antonio becomes the youngest death row inmate in the country after he gets caught up on a bizarre crime instigated by two older men.

p. 157: America has stepped up its practice of incarcerating children. In better times, if a 13 or 14 year old committed a heinous crime or if the crime was Black on White violence, there was a fair chance that the teen might be tried as an adult.

p. 159: Stevenson recounts several stories of youth who were jailed and executed for crimes they did not commit. He goes on to suggest that these miscarriages of justice may be a return of the ghost of lynching. Following the Civil War, Whites feared that newly freed Blacks would avenge themselves on their former masters and Whites in general. Whites also feared Black leadership and Black White romances and mixed race children. Whites projected on Blacks the inclinations towards the very cruelties that they had inflicted—rape, autocratic governance, laziness, aristocratic pretensions, and violence.

p. 159: The 1980’s super-predator scare jolted legislators into taking down legal barriers which protected children from arrest and excessive incarceration.

Excursus: Much racial oppression uses false information as a pretext to implement oppressive practices, which fall disproportionately on Blacks. Drugs, youth violence, the rise of gangs, drug use, caravans and the like are often exaggerated and the truth is never as glaring as the initial distortion.

p. 161: The chapter ends with a letter from Ian expressing appreciation for a photo shoot that Stevenson arranged for. Ian, who has been in solitary confinement finds the photo shoot significant because it certifies that he is alive and not lost to the world in prison.

Chapter 8 “All God’s Children” Summary:

Chapter eight focuses on the shameful American use of life imprisonment for youth who committed crimes while still minors. The chapter summarizes three such children’s stories. All three were driven to their crimes by desperation. Stevenson explains that public anxiety over mythical super-predators has led to laws which ramp up the severity of sentences. Long-term confinement is destructive of people’s humanity, especially the humanity of kids. Ian’s touching letter about a photo shoot ends the chapter.

Chapter Nine: “I’m Here”

p. 163: The date for Walter’s post-conviction evidentiary hearing arrives and will be greatly enhanced by Ralph Myer’s testimony plus the trove of exculpatory evidence lifted from the Monroe County sheriff’s office and courts. The drama early in this chapter revolves around the question whether the unpredictable Myers will tell the truth. Around this time Brenda Lewis comes to work with Stevenson’s law office as a paralegal. Lewis is a disillusioned Montgomery police officer who quits her job in order to work with Stevenson. Chapman, the new DA, also works to strengthen the state’s case by bringing aboard Don Valeska, a combative prosecutor. The judge, Thomas B. Norton Jr., is also new. Stevenson feels that all of his opponents, including the police, Prosecutor’s office, and judge are weary of him.

Excursus: I think all of these characters are still alive and working. This book chronicles them in a terrible light. Stevenson’s irenic prose conceals a sharp and deserved attack on people’s reputations. To wonder Stevenson was receiving death threats.

p. 164: The judge gives Stevenson 3 days to present his case, not the seven he had requested.

p. 165: Ralph Myer is a loquacious and unreliable character. Stevenson and O’Conner are concerned that he will give a bizarre and counter-productive performance on the witness stand.

p.. 166: The courtroom is crammed with people, including Walter’s family and friends.

p. 167: The judge denies Stevenson’s request to keep officers outside (sequestration) during testimony so when they hear testimony they don’t adjust their own stories.

p. 168: Stevenson, hobbled by the judge’s ruling against his requests, decides to begin with a statement. The statement lifts up the importance of Ralph Myer’s testimony, which Stevenson is prepared to thoroughly discredit.

p. 169: Stevenson recounts Myers fanciful testimony, which introduces a third man at the cleaners. Stevenson states that the state knew the third man was fictitious because they never went after him. The implication is that the state, knowing Myer’s story was a fabrication, selectively used only the portions that justified arresting and charging McMillian.

p. 171: After vigorous questioning and cross-examination, Myers comes through gloriously with the truth.

p. 172: Stevenson calls Clay Kast the mechanic to testify whether Walter’s truck was a “low rider” at the time of the crime. Also called is the police officer whose description of the scene contradicted Myers original false testimony. Prosecutor Pearson has pressured Ikner to testify falsely.

p. 173: Present at the hearing are Winnie, Walter’s wife; Armellia, his sister; Giles, his nephew; and other relatives.

p. 174: On the hearing’s second day, officials exclude Walter’s supporters. They also have added a menacing metal detector and a German Shepherd Dog at the courtroom’s entrance.

p. 176: Mrs Williams, an elegantly dressed older Black lady, enters the courtroom. But she leaves terrified at the sight of the dog.

p. 177: Psychiatrist, Omar Wohabbat, one of Myer’s therapists, testified that Ralph had stated in a counseling session that he lied. Four doctors are called and each testifies that Myers told them that someone had pressured him to give false testimony.

p. 178: The hearing’s 2nd day ends well and has kept to Stevenson’s time schedule.

p. 179: It turns out that Mrs. Williams marched with MLK at the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma and had experienced dogs personally in her days of civil rights activism. Triumphantly, Mrs. Williams is able to walk past the dog on the trial’s third day.

p. 182: After 2 ½ days of exculpatory testimony, Stevenson presents tape recordings of Myer’s interview with Benson and Ikner who coax him on tape to lie. The trial finishes with the state presenting very little rebuttal.

p. 185: Stevenson describes a brief respite where he and Michael visit a pristine beach on Alabama’s Gulf Coast. As the lawyer’s talk their feeling of release and relaxation gives way to anxiety as they think of the amount of rage they have stirred up, which might be directed to Walter and to them.

Chapter 9: “I’m Here” Summary

The dramatic ninth chapter recounts the three days of the post-conviction evidentiary hearing. The hearing is a success for Walter’s cause because Stevenson brings massive testimonial evidence that proves that the police have pressured Ralph Myers to lie about Walter’s truck ride to the cleaners and subsequent murder of Ronda Morrison. Noteworthy testimonies come from Ralph himself, four psychiatrists, an shop mechanic, and tapes of recordings of police pressuring Ralph. Stevenson interweaves the courtroom drama with the story of Mrs. Williams, a survivor of police violence in 1965 at MLK’s famous march on Selma’s Edmund Pettis Bridge. Terrified of the police dog present in the courtroom, Mrs. Williams achieves a personal triumph in courage when she is able to step past the animal. The chapter ends on a Gulf beach when the attorneys begin to worry about all the threats of violence they are receiving.

Chapter 10: “Mitigation”

p. 186: The high numbers of people in prison are composed largely of drug offenders, the poor, and mentally ill.

p. 187: Stevenson gives a brief history of mental health care. In the late 1800’s mentally ill people in prisons were released to mental hospitals. By the mid 20th Century, doctors use anti-psychotic drugs, such as Thorazine, to treat mental patients. By the 1960’s and 70’s, legislatures enact laws making it difficult to hospitalize someone involuntarily. This de-institutionalization coincides with the advent of mass incarceration. Mentally ill people outside of hospitals or jails are easy targets for the justice system.

p. 188: Half of America’s prison population has a diagnosed mental illness. Twenty percent has a serious mental illness and prisons are terrible environments to recover from a mental illness. For example, mentally ill inmates have difficulty complying with the rules, endure abuse by other prisoners, and are misunderstood by the guards.

p. 189: One such mentally ill death row prisoner was George Daniel who was represented by Stevenson. Daniel had a brain injury from an automobile accident. In the days after the accident, George began hallucinating and behaving bizarrely. George’s unhappy story gets much worse as he wrestles a police officer whose gun discharges, killing the cop. George is charged with capital murder. He becomes psychotic.

p. 190: The doctor examining George determines that he is malingering, which allows the murder trial to go on.

p. 191: George ends up on death row.

Excursus: George’s situation requires him to tolerate incompetent help, notably the doctor and bickering attorneys. All services to the poor are of poor quality—the store front tax preparer, pawn shop, medical help, churches, fast food outlets, thrift stores, legal help, pay day lenders and so on. The Wednesday morning ministry works to overcome the avalanche of poor assistance.

p. 191: At length, Stevenson got George’s conviction overturned. He was retried.

p. 193: Jenkin’s Case—a mental illness inmate who had a terrible childhood. Stevenson offers a parenthesis on the South, which has always found ways to counter Black progress. He recalls the 1950’s and 1960’s at the start of the Civil Rights movement when southern states erected confederate flags and put Jefferson Davis’ birthday on the calendar. These are designed to raise the ghost of slavery and Jim Crow to menace Blacks.

p. 194: Stevenson tells story of the judge who says aloud in court that he wonders if anyone would speak up for “Confederate Americans.”

p. 196: Several pages here are devoted to describing the hostility that greeted Stevenson as he attempted to visit. Much of this chapter is dedicated to the symbolic ways that segregation, racism, and oppression are kept in place through symbols, flags, statues, and even bumper stickers.

p. 198: Stevenson describes Jenkin’s post-conviction hearing esp. the psychiatric expert witness.

p. 199: The hearing goes well. Following the post-conviction hearing, but before the ruling, Stevenson goes to visit Jenkins. Arriving at the prison, Stevenson spots a threatening truck festooned with menacing bumper stickers.

p. 200: One guard’s demeanor was completely different—pleasant and accommodating. This guard had overheard Stevenson speaking with his client about the difficulty of growing up in foster care. The listening guard felt a oneness with Avery Jenkins, for he like the inmate had grown up in foster care. Significantly, while transporting Jenkins, the formerly nasty guard stops in a Wendy’s and buys his prisoner a milkshake.

p. 202: At chapter’s end, Avery wins a new trial and transfers off of death row to a mental health prison. The guard eventually quit his job and was never seen again.

Chapter 10: “Mitigation” Summary.

This chapter’s overarching theme concerns the high numbers of mentally ill persons who are not only in prison, but on death row. The chapter provides luminous insights, which shed light on why America’s prisons are populated with mentally ill people. One reason is the historical interaction between prisons and mental hospitals. Change in one usually entails adjustment in the other. The author ties the chapter together by two cases involving mentally ill inmates who land on death row mostly because of their horrible childhoods. In the second case, that of Avery Jenkins, Stevenson encounters a menacing prison guard, who drives a truck emblazoned with Southern attitude bumper stickers and symbols of the confederacy. The nasty guard experiences an attitude shift after he overhears Stevenson’s conversation with his foster-home raised client. The guard realizes that his experience is akin to that of the prisoner a realization that brings a noticeable change of attitude.

Chapter 11: “I’ll Fly Away”

Stevenson’s law office is expanding and now receiving credible bomb threats, which unnerve the new staff. The threats have enough credibility to cause evacuations. They’re believable following the bomb blast deaths of attorney Robert Robinson and Judge Robert Vance. Mail in bombs also exploded at the Atlanta courthouse and a civil rights office. At EJI mailed packages are inspected.

p. 204: Stevenson and O’Connor were also followed on their drives to Montgomery.

p. 205: Judge Norton’s office faxes its response, a denial, to Walter’s post-conviction evidence hearing. The judge cites Ralph Myers’ misdemeanor and outside influences as the basis of the ruling that Myers had perjured himself.

p. 206: The Alabama Court of Criminal Appeals looks more promising for a positive ruling in Walter’s case.

p. 207: By this time, Stevenson has won several cases in this court. He describes his partner Michael O’Conner’s departure and the coming of his replacement, Bernard Harcourt.

p. 208: Stevenson, concerned about Walter’s post-release safety in his community, decided to “publicly dramatize” his wrongful conviction, meaning that he is going to try to get national media coverage of Walter’s story. Stevenson reflects on the fact that publicity, which embarrasses the court traditionally attracts robust counter-attacks, such as John Patterson’s lawsuit for defamation. Defamation lawsuits place a deadening hand on news coverage of civil rights activism.

p. 209: The Landmark ruling of New York Times v. Sullivan has enhanced press freedom by freeing it somewhat from lawsuits. To prove defamation, plaintiffs must prove malice on the part of the reporting. Newspapers must be knowingly reporting untruth in order to defame in order to be guilt of defamation.

Excursus: This might be a clue to the animosity that Trump supporters feel towards the media.

p. 210: Local newspapers insinuate that Walter may have committed several other murders, was a drug dealer, committed sodomy, and other outrageous suggestions. Stevenson feels that the truth about the crime was of little interest for many.

p. 211: Stevenson has an audience outside the South by this point. He gives a speech at Yale Law School and is contacted for stories by the Washington Post and 60 Minutes. Generally, however, the South dislikes the media and newspaper stories, sometimes accelerating the justice process. At length 60 minutes sends a crew to Montgomery.

p. 212: A core difficulty in challenging the courts and local press is both’s tendency to push back.

p. 213: “…the case so traumatized the Black community…” Like lynchings before, the jailing and executing of Black community members serves as a repressive measure.” The 60 Minutes coverage seems to worry DA Chapman, who orders an ABI investigation into the evidence. This sequence of events is to prove to be a turning point in Walter McMillian’s case.

p. 214: The ABI determines that there is no possibility that McMillian killed Morrison. Stevenson further learns that Hooks and Hightower’s trial testimony was false.

P. 215: Hooks lied, saying that Stevenson, pressing him to change his testimony, had promised him money and a condo in Mexico. The ABI guys now want to solve the entire murder and they enlist Stevenson’s help.

p. 216: An anonymous caller engages the ABI guys in long phone conversations. He claims falsely that he knows where the murder weapon is.

p. 217: The ABI guys name a man they believe to be the murderer and seek additional information from Stevenson. Despite the accelerated pace of the case, the ABI guys want Walter to stayon Death Row until the real killer is caught.

By this time the State Attorney General takes on the case

Excursis: “No lie can live forever” –Bryan Stevenson

p. 219: Stevenson reflects on the importance of hope when awaiting justice.

p. 220: The Criminal Court of Appeals rules in Walter’s case. A new trial is ordered. Walter, of course, is pleased. He and Stevenson spend a light moment while they are together.

p. 222: Minnie doesn’t think Walter should return to his home and old neighborhood, due to shadowy malice and racism that inhabits his world.

p. 223: Tom Chapman is gracious just before Walter’s release and requests the honor to shake Walter’s hand.

p. 224: There is a brief hearing, which formally allows the judge to dismiss all charges against Walter. Stevenson feels at this triumphal moment an unforeseen agitation, which grows into rage, which Stevenson voices as a final comment to the packed courtroom. Stevenson’s rage is his anger over the vast suffering that has come of this miscarriage of justice.

p. 225: There is a large crowd and buoyant mood that accompanies Walter’s release. The celebrations include several moving expressions of solidarity with Walter, such as the death row celebration, when Walter gives away some of his prison possessions.

Chapter 11 “I’ll Fly Away” Summary

This chapter recounts the final legal steps that culminate with Walter’s glorious release. The chapter begins with the disappointment of Judge Norton’s denial of a stay, despite the massive case Stevenson makes proving that Ralph Myers has lied about Walter’s involvement. Stevenson then moves to the risky, but eventually decisive, tactic of involving national media. Media attention nudges local courts out of their intransigence. Sixty Minutes carries Walter’s story despite continued local media insinuations of Walter’s guilt. Stevenson’s appeal to the State Court of Criminal Appeals gets the ABI involved. Its investigation quickly proves Walter’s innocence of the Morrison murder. A favorable ruling from the Appeals Court orders a new trial, which the local jurisdiction is disinclined to pursue. A brief hearing secures Walter’s release. Several non-legal themes thread through this chapter, including the persistence of shadowy threats to Walter’s family and Stevenson’s office, the role of media publicity in court cases, and the importance of hope in enduring through such long struggles for justice.

Chapter 12: “Mother Mother”

p. 227: Marsh Coleman and husband Glen, together with their many children, are poor White Southerners whose home is destroyed by Hurricane Ivan. While in a bathtub, Marsha delivers a stillborn infant. She and Glen bury the infant on their property.

p. 230: A meddling neighbor arranges for police to investigate. The infant’s body is exhumed and determined by a medical examiner to have been born alive and able to survive.

p. 231: Marsha Coleman is arrested and charged with capital murder. All women on Alabama’s death row are convicted because of infant deaths or deaths of abusive partners.

p. 232: Steven discusses the expansion of mother prosecution, where infants are found dead. Other high publicity cases include Andrea Yates, Casey Anthony, and Susan Smith. The United States has a particularly high rate of infant mortality.

p. 233: Communities are on the lookout for bad moms to put in prison. Stevenson helped to defend Diane Tucker and Victoria Banks.

p. 234: Other forms of child abuse are criminalized. These include exposure of children of fetuses to drugs. These stricter laws led to thousands of arrests in poor communities.

p. 235: Marsha Colby ends up in Julia Tutwiler Prison for Women. Tutwiler is over-crowded. Fact: 646% increase of incarcerated women between 1980-2010.

p. 236: Most women, mostly mothers, are incarcerated because of drugs or property crimes.

p. 238: Tutwiler inmates endure high levels of sexual violence.

p. 238: Marsha Colbey’s appeal: Attorneys Charlotte Morrison and Kristen Nelson, at EJI meet with Marsha. The sexual violence at Tutwiler is what keeps emerging during their visits. Eventually EJI interviews 50 women locked up at Tutwiler to discover rampant sexual abuse.

Pl 240: Marsha is freed after 10 years of wrongful incarceration. EJI wants to honor Marsha at its annual fund-raising banquet. Previously John Paul Stevens and Elaine Jones were honorees.

Chapter 12, “Mother Mother” explores the rise and unfairness of incarceration for women in America. Marsha Coleman’s is one such sad story. She was convicted and sentenced for a long time after giving birth to a stillborn infant and burying her. The chapter provides a brief expose of Tutwiler Prison for Women, an institution that holds women convicted mostly of drug and property crimes. Sexual abuse is rampant at Tutwiler. The chapter ends triumphantly with Marsha, released through EJI’s efforts, receiving the prestigious EJI annual award.

Chapter 13: “Recovery”

p. 242: Walter’s exoneration and release attracts much national media attention. Stevenson believes that media coverage following release helps former death row prisoners to readjust better. Since 1976, fifty persons have been released from death row and released from prison. Not many have been covered by news outlets.

p. 243: Walter and Bryan testified before Senate Judiciary Committee and spent time traveling together in response to the publicity that Walter’s case provoked.

p. 244: At length, Walter moved back to his property, took up the logging work and filed civil suits against the local justice system. Most people released from prison get no counseling or compensation.

p. 254: News outlets claimed Walter was seeking 9 million dollars in compensation. His neighbors, in turn, were infuriated by this number.

p. 246: State and federal courts have made local justice officials who sentence an innocent person immune from civil suits.

p. 247: Courts up and down the chain have been reluctant to allow prosecutors and judges exposure to civil suits.

p. 248: While cutting wood, Walter was struck by a tree limb, got a broken neck, convalesed for a time in Stevenson’s home, and returned to his old life, but this time collecting and reselling car parts and scrap iron.

p. 249: Walter and Stevenson go to Chicago for a conference on exonerated former death row prisoners. By that time, DNA evidence was securing the release of many felons. Death penalty repeal or a moratorium on executions seemed possible.

Stevenson starts teaching at the NYU School of Law.

p. 250: In 1994, legal aid to death row prisoners was eliminated. This put EJI in a squeeze, but private funding continued and the talented staff carried on in its important work. EJI received the Olof Palme International human rights award. EJI and Stevenson’s recognition affords him conversations with many people.

p. 255: The chapter concludes with two contrasting scenes that emerged with the Human Rights Award. First, in an exquisitely written description, Stevenson conveys a beautiful moment when High School students sing to him in gratitude for his speech. Second, is the Swedish camera footage of Walter tearfully and in anguish describing his years on death row.

Chapter 13 “Recovery” Summary

Chapter 13 describes Walter McMillian’s return to his home and life. An accident forces Walter to earn his living by collecting scrap metal. The chapter highlights the contrast between the public disinterest in and paltry compensation of the wrongly convicted with the accolades that Bryan was receiving. The chapter ends with a Transfiguration-like moment of grace as a Swedish High School sings to Bryan. This exquisite moment is contrasted with Walter’s anguish as he recounts for the Swedish film crew his experience with Southern justice and the fear of death row.

p. 256: Stevenson describes Lena Bruner’s dual victimization, first by three boys who robbed her, and then by two men who raped her. One of the boys, Joe Sullivan is indicted as an adult for sexual battery.

p. 257: The lies of Joe’s comrades, a palm print, destroyed DNA evidence, a judge’s decision to try the boy as an adult, poor legal representation, and a hasty trial all lead to Joe’s conviction to life imprisonment.

p. 258: Joe is mentally disabled, a child abuse victim, and comes from a chaotic home.

p. 259: In prison, Joe is repeatedly raped. He attempts suicide. Stevenson challenges Joe’s death in prison sentence as a violation of the cruel and unusual punishment principle in the 8th Amendment.

Stevenson visits Joe at Santa Rosa Correctional Facility, a notorious prison.

p. 260: Imprisonment is profitable and hundreds of prisons were opened between 1990 and 2005. Imprisonment in America is used to solve many problems.

p. 261: Stevenson describes cages at Santa Rosa, used to confine prisoners. Joe, wheelchair bound, gets stuck on the door of his cage as he attempts to leave. One wonders how long Joe has been in the cage.

p. 264: Stevenson decides to petition for Joe’s release based on the cruel and unusual punishment he is receiving.

p. 264: The Narrative shifts to Evan Miller’s conviction in Alabama. Miller’s crime is the murder of Cole Cannon, an adult and drinking partner with Evan and another youth. Following a fight, the younger boys beat Cannon and set the structure on fire. Cannon dies. Even ends up with life imprisonment without parole.

p. 265: Stevenson petitions the court after Evan’s conviction requesting a lighter sentence on the basis of his age.

p. 266: By way of a side note, most felons who commit violent crimes grow into a more adult attitude, which regretfully wonders how they could have been so cruel in their younger years.

p. 267: Recounting his own grandfather’s senseless murder by a youth, Stevenson reflects that the difficult circumstances of poverty have impact on young people that somewhat explains their crimes.

p. 268: Stevenson quotes expert opinion on the chemical changes in adolescents that make them take risks and seek stimulation.

p. 268: Courts that Stevenson has dealt with are so intent on exacting punishment, that is necessary to remind them of the differences between adults and adolescents.

p. 269: The mixture of adolescent brain chemistry and poverty, plus environmental violence, and the absence of caretakers, is a flammable mixture for youth.

p. 270: Stevenson reflects on work his organization did to gain relief for younger incarcerated people in view of developmental differences between adolescents and adults.

p. 270: Stevenson appealed to the Supreme Court on behalf of Joe and another Florida case, that of Terrance Graham.

p. 271The case filed with the US Supreme Court is joined by many medical and psychological associations.

Chapter 14 Summary:

This chapter’s focus is on the developmental difference between adolescents and adults. This difference plus the hostile homes and neighborhoods endured by many American children are a combustible combination which sometimes leads to violent crimes that the perpetrators themselves find unexplainable as they mature. Stevenson by this stage is working on a national level on behalf of incarcerated youth and he makes appeal to the US Supreme Court on behalf of youthful life-sentence prisoners.

Chapter 15: “Broken”

p. 276: Walter is stricken with dementia and declines quickly. As he declines, the EJI social worker works to find him suitable institutional care.

p. 277: Meanwhile, EJI’s busyness and the tensions of its workload rise. A handful of inmates are reaching the ends of their appeals. Alabama’s electric chair looms over many of Stevenson’s cases. Stevenson is waiting for the Supreme Court to rule on Joe Sullivan’s case.

p. 280: Stevenson visits Walter in a “memory” facility. Walter’s confusion drives him back to relive his death row terrors. This is taxing for Stevenson.

p. 281: Alabama does not follow the civilized world’s slow abandonment of execution, but maintains its place as having the highest execution rate in the country. Electrocution, gas, firing squads, and hangings have given way to lethal injection in most places. Even lethal injection, however, is beginning to be understood as painful and problematic.

Pharmaceutical companies, domestic and European, have withdrawn their products from being sold to the American prison system. Problems arise because drugs are scarce. Substitutes, for example, have more problems. For a time, executions decline. But a Supreme Court decision loosens restrictions on various drugs and combinations allowable for Capital Punishment.

p. 285: Stevenson is exhausted and his efforts to win a stay of Jimmy Dill’s execution fail.

p. 286: As Stevenson listens to Dill on the phone with his speech impediment, he recalls a boyhood incident when he was scolded by his mother for laughing at another child with a speech disability.

p. 288: Stevenson is overcome with the brokenness and inhumanity that engulfs his life. He wants to escape.

p. 288: Stevenson is overcome with the brokenness and inhumanity that engulfs his life. He wants to escape.

p. 290: Stevenson, with his work with the most desperate of prisoners and the most hateful angry police and courts is engulfed by brokenness. He wants to escape.

p. 291: Owning up to our brokenness makes it less likely that we would want to kill the people who themselves are the most profoundly broken. Those in our world who appear to have been beaten into a subhuman state attract the murderous rage of others, who themselves are broken. Hurt people hurt people. If we acknowledge our brokenness we would no longer take pride in mass incarceration. Stevenson cites the Psalms 51, “Let the bones which thou hast broken rejoice.”

p. 293: As Jimmy Dill is executed, Stevenson is having these thoughts. He moves on to the insight that a person’s brokenness is essential to that person’s humanity. Stevenson reflects on Rosa Parks, Mrs. Carr, and Mrs. Durr as they talk and as he listens.

p. 294: With these reflections, especially on what he flashes back to and the three ladies’ conversation, Bryan finds himself hopeful again. On the car drive home Stevenson hears a radio preacher talking about the text in 2 Corinthians, “My grace is sufficient for you and my power is made perfect in weakness.” The web of hurt and brokenness is also the web of healing and mercy. He ends speaking of grace, which goes to those made perfect in weakness, Stevenson finds energy to book a speech to high school students, significantly on the topic of hope.

Chapter 15: “Broken” Summary

The most reflective and profound of the book, this chapter begins with Walter’s sudden onset of dementia. The sadness culminates with Jimmy Dill’s execution, a tragedy Stevenson and his organization cannot prevent. Piled under with work and executions moving inexorably forward, Stevenson is the last to speak with Jimmy Dill. On the brink of his execution, Dill gushes thanks for Stevenson’s efforts.

In tears, Stevenson hangs up the phone feeling the full onslaught of the shabbiness and evil of the world he inhabits. He further realizes that this environment and his daily tasks have broken him as well. Stevenson reflects on human brokenness as the opening for grace. As Dill’s execution goes forward, Stevenson recalls being invited to listen to three older Black ladies, including Rosa Parks. All three were civil rights warriors who have somehow made it to old age because they have not let go of hope. Lifted by this memory and a radio sermon on the 2 Corinthian text, “My grace is sufficient for you and my power is made perfect in weakness,’ Stevenson finds energy to book a speech to high school students. The speech will be about hope.

Chapter 16: “The Stonecatchers’ Song of Sorrow”

p. 295: In 2010, the Supreme Court agreed with EJI that life imprisonment without parole imposed on children convicted of non-homicide is cruel and unusual punishment and unconstitutional. This development opens the door for meaningful opportunity for release. Two years later, EJI won a constitutional ban on all mandatory life-without-parole for children. This makes thousands of convicted youth eligible for reduced sentences.

p. 297: Stevenson’s success in the Supreme Court creates a long gap of 18 months with no executions in Alabama.

p. 298: The US prison population starts to decline in 2012. Stevenson launches his race and poverty initiative. Part of this is the development of a Black history initiative.

p. 298: Four American institutions that shape our approach to race and justice

slavery

violence following Civil War

Jim Crow

mass incarceration

p. 301: Stevenson reports on additional growth of the EJI.

p. 303: Stevenson represents prisoners at Louisiana’s Angola Prison, a notoriously violent and brutal prison. His organization had a regional or even national reach. Stevenson decides to appeal for release of old-time cases of prisoners who had been children when they were arrested. He describes Joshua Carter and Robert Caston’s cases.

p. 304: The New Orleans court was extremely chaotic with little time discipline and general chaos. This has the effect of keeping prisoners locked up because of the chaos of the environment.

p. 305: There were endless issues that arise in the chaos that kept Mr. Caston Sullivan incarcerated. When their release is announced the courtroom, including the judge, irrupts in applause.

p. 307: Waiting for the paperwork related to Caston and Carter’s release, Stevenson encounters an older Black woman who he has spotted in the courtroom. She wants to give Stevenson a hug. She then explains that her grandson has been murdered. Curiously, the incarceration of the killer brought her even more pain. After a bit, she tells Stevenson that she is like the stone-catcher who catches the stones people throw at each other.

Chapter 16, “The Stonecatchers’ Song of Sorrow” Summary

Chapter 16 puts before the reader the sad and beautiful work that Bryan is doing and that many do who labor in an evil world to win the release of people. He begins by describing some breakthrough Supreme Court judgments that make it possible for hundreds of people, having committed crimes as minors, serve endlessly in prison. The chapter details some of the maneuvers used to secure release of Joshua Carter and Robert Caston, two elderly inmates who had lived their adult lives in prison. Stevenson describes a deeply graced moment when the release decree is read and everyone in the courtroom bursts in applause. This moment opens a vista on the glorious truth that everybody is wearied, confined, and broken by the justice system and release for one becomes a little release for all. The chapter and book culminates with a tender chat between Stevenson and an old Black lady who lost a grandson to murder. Unexpectedly, she feels grief for the perpetrators. She now comes to the court to try in her small way to bring some good to the situation, to catch the stones that people throw at each other. The metaphor of catching stones, reminiscent of the stoning of the woman caught in adultery, is an apt way to describe Stevenson’s work and the work that his book invites the reader to take up.

Epilogue

The book’s epilogue consists of a brief description of Walter’s funeral. Walter’s life, anguish, and release encapsulated two spiritual themes in Stevenson’s work—that fear and hate distort justice and that hope allows everyone touched by touched by brokenness to keep moving towards deliverance.Posted onDecember 8, 2018Categories