Eight Key Takeaways from Ibram X. Kendi’s, Stamped from the Beginning

Ibram X. Kendi’s, Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America is an encyclopedic and well-organized survey of race through US history. The book is a timeline. It begins in the 15th Century Age of Exploration and finishes with Obama’s election. In-between there is a massive assemblage of historical episodes.

It’s this clear organization that makes it easy to summarize Stamped from the Beginning in this post for anyone who is thinking about reading the book or for someone who needs a quick survey of what it’s about.

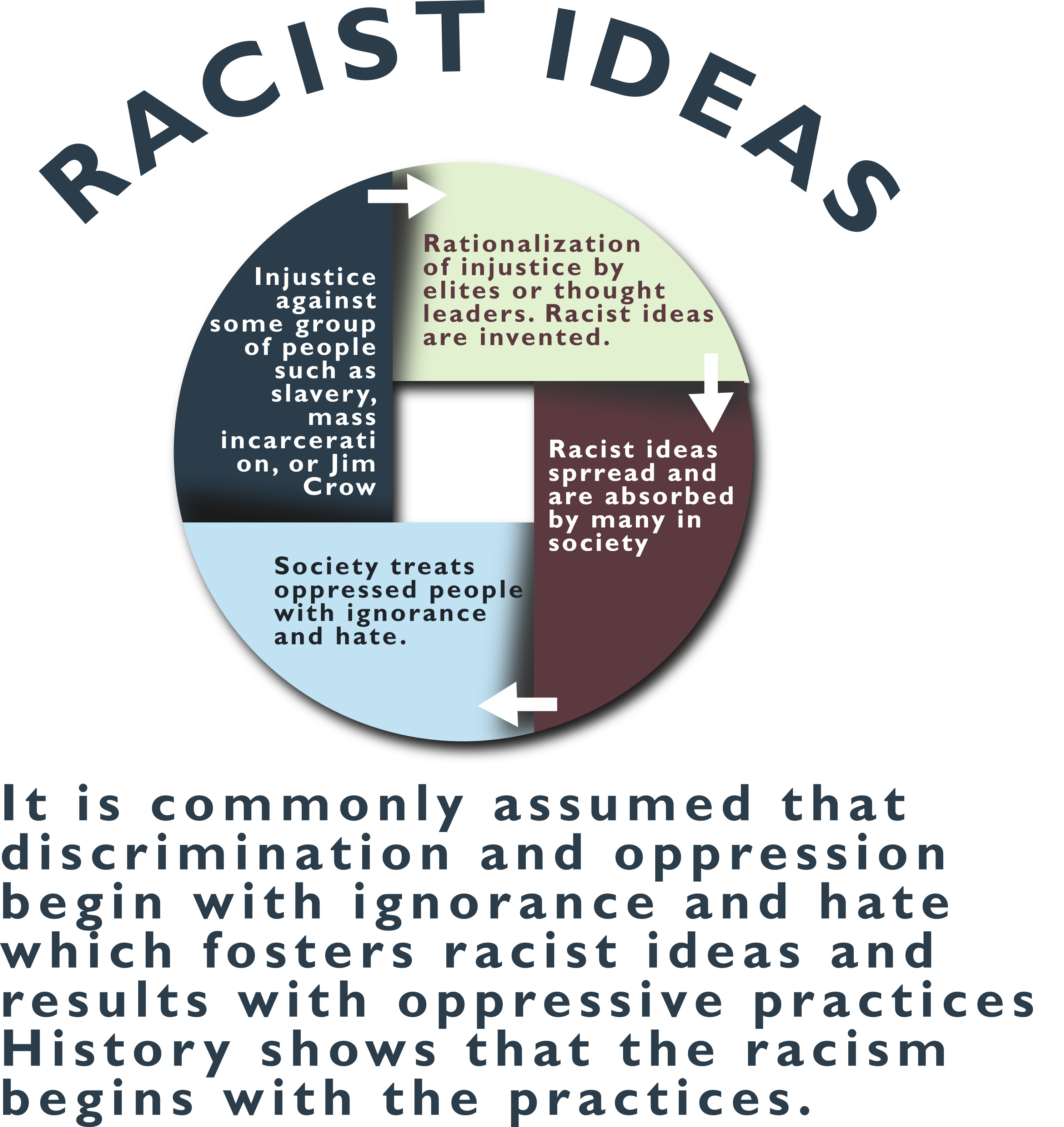

Happily, for Kendi’s reader, this huge pile of historical data never collapses into a confusing mess. This is because he keeps his readers on track by letting them know in the preface what principles they will be discovering as they wade through the balance of the book. Racism, in other words, has predictable patterns. For example, people concoct racist ideas in order to rationalize, say, slavery. Oppression comes first. Then people invent some explanation that defends it. That’s one of the principles. The preface gives away Kendi’s conclusions. Then when readers move through the various periods of American history, these patterns keep reappearing.

Kendi’s history is chronological, and divided into five sections, each section corresponding to a historical person’s lifespan. These lives—Cotton Mather’s, Thomas Jefferson’s, William Lloyd Garrison ’s, W.E.B. Dubois’s, and Angela Davis’s–serve as “windows” into the drama of race that was being played out in their respective eras.

It’s this clear organization that makes it easy to summarize Stamped from the Beginning in this post for anyone who is thinking about reading the book or for someone who needs a quick survey of what it’s about.

So what will the reader of Stamped from the Beginning be learning?

The Takeaways

1. What is a racially just society?

It’s a society that sees all races, notably African Americans, as equal biologically, culturally, and behaviorally. This is a classic “simple but not easy” goal. What makes equality not easy is that it allows for differences. In other words, Black people will always look like Black people. The features and skin color of African descent people will not be a sign that they have fallen short in some way. They will keep traditions and relate with one another as African-descent people. The goal of equality will not be a hidden way of pressuring Black people to become White. The differences in people of different backgrounds will not be grounds which prove inferiority or need White intervention to fix. Blacks will be free to be Black, free to have the strengths and weaknesses that are part of the human condition, without these being deemed as evidence of inferiority. As a corollary to this is Kendi’s assertion: When you truly believe that racial groups are equal, then you also believe that difficulties such as poverty, criminality, or limited life-spans, which befall all or most Blacks, must then be the result of racial discrimination.

2 Who are the racists and who have broken free from this problem?

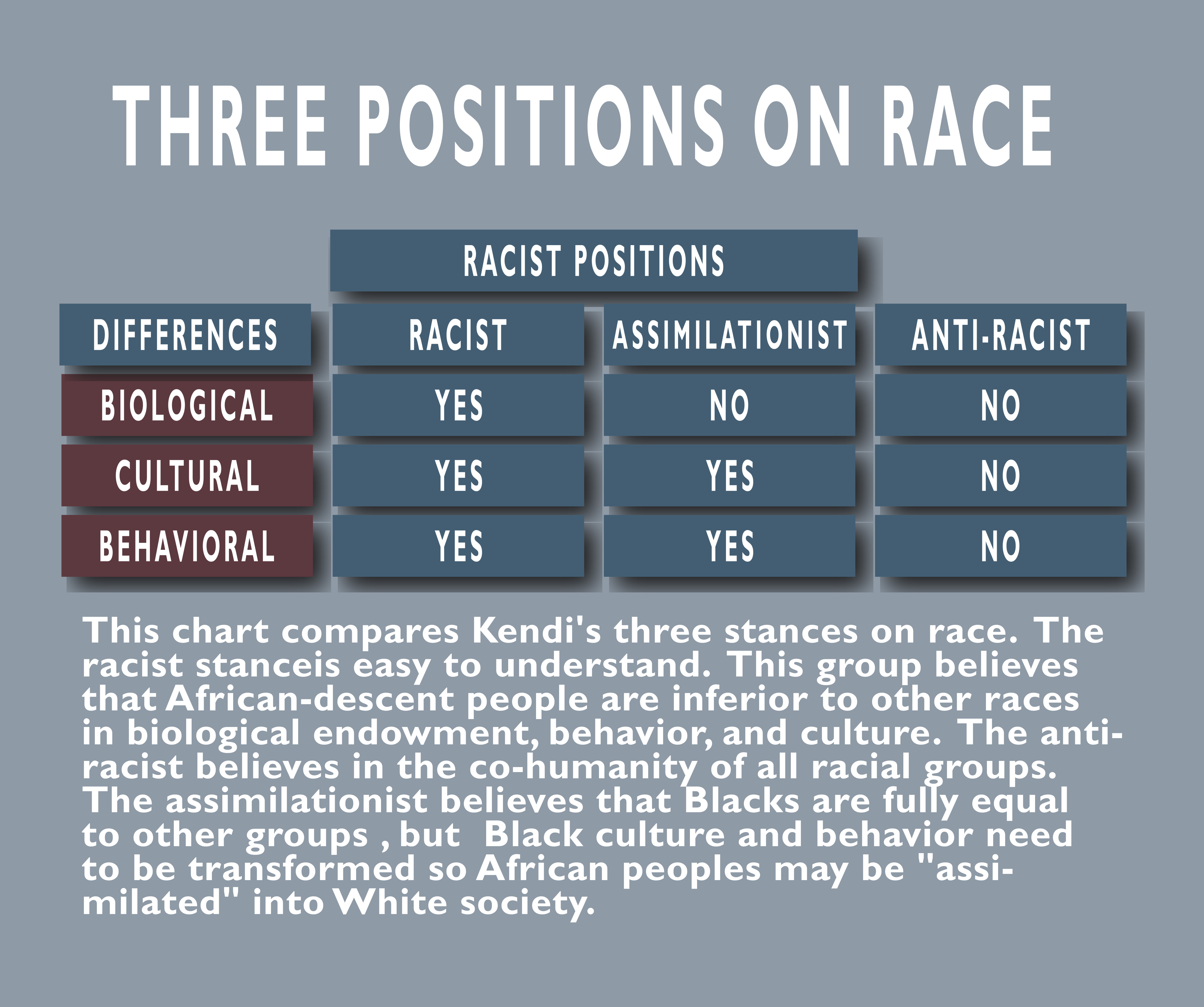

These are categories of people:

- racists

- assimilationists

- antiracists.

Racists believe that African descent people are inferior biologically, culturally, and behaviorally and should occupy a place in society that reflects their inferiority. Antiracists believe in equality of all races in all three dimensions. Assimilationists are a middle category with aspects of both operating at once. Assimilationists typically works for improvement in Blacks and their social condition. At the same time assimilationists assume that Blacks are inferior in some way. One author described the assimilationist position as the “racism of good intentions.”

Almost everyone, including Kendi himself, falls into the assimilationist category. Famous assimilationists, like W.E.B. Dubois started with the assimilationist position on his journey toward antiracism. Abraham Lincoln is a towering example of the assimilationist form of racism. Lincoln famously issued the Emancipation Proclamation which abolished chattel slavery. Lincoln also said during the Lincoln-Douglas Debates:

There is a physical difference between the white and black races which I believe will forever forbid the two races living together on terms of social and political equality. And inasmuch as they cannot live, while they do remain together there must be the position of superior and inferior, and I as much as any other man am in favor of having the superior position assigned to the white race.

The assimilationist category is the most interesting and Kendi is continually returning to it and deepening its nuances. The assimilationist, as the name implies, seeks justice for blacks by drawing them into White society. The assimilationist is tainted by ideas of Black inferiority that are embedded in his or her effort to help Blacks. Simply put, a white advocate for social justice may enthusiastic work to “help” African descent people by subtly insisting that they behave culturally White. Alternative the social justice advocate may strive energetically to help African-descent people in such a way that suggests Blacks cannot help themselves without White assistance.

3. How can racial justice happen?

Every advance for Black Americans is undercut by some kind of concurrent regression. When slavery ended Southern Whites worked feverishly to set up new forms of captivity, notably the share cropping system or Jim Crow. Civil Rights was undercut by mass incarceration. The election of a Black President was answered by the rise of White Nationalism. Recent thinkers who have coined expressions such as Afro-pessimism, re-enslavement, the afterlife of slavery, and the like to express the “one step forward, one step back” character of racial justice in America.

4. What is a racist idea?

A racist idea is some report about Black people that leads to the conclusion that they are inferior in some way and in turn supports injustices that put Blacks at a disadvantage and keeps them in low caste status. Here’s Kendi’s definition:

A racist idea is “an idea suggesting that Black people, or any group of Black people, are inferior in any way to another racial group.”

5. Who thinks up racist ideas?

It’s invariably the smartest people, the intellectuals, the thought-leaders. They are scientists, political leaders, social justice advocates, authors, and clergy. One would think that racism arises out of ignorance and cruelty. Just the opposite is the case. In the early 15th Century, Prince Henry the Navigator of Portugal ventured, via the Atlantic Ocean to what is today Ghana, the first modern-era voyage to sub-Saharan Africa. Those early expeditions back and forth from West Africa launched the European slave trade.

In 1452, Prince Henry’s nephew, King Afonso V, commissioned Gomes Eanes de Zurara to write a biography of the life and slave-trading work of his “beloved uncle.” The resulting tome, The Chronicle of the Discovery and Conquest of Guinea, not only recorded Henry’s ventures but also speculated about the origin and nature of the African peoples with whom Henry had come into contact.

So, the book usefully chronicled Henry’s adventures. But it also served as an introduction of the African peoples to a Europe that had only just come to realize that there was a place south of the Sahara Desert. Zurara depicted his uncle’s Black captives as sub-human and suited for slavery. His book and ideas were consumed widely and uncritically for decades throughout Europe and planted the core racist idea of African inferiority.

The pattern of sophisticated people speculating beyond their area of expertise about Blacks is traceable to the present. Kendi elaborates how racist ideas infect the thinking of Cotton Mather, Thomas Jefferson, Immanuel Kant, William Lloyd Garrison, Abraham Lincoln and on and on.

6. The vicious cycle of racist ideas.

Intuitively, one might think that racist ideas come first and then racial injustice follows. Actual history suggests the opposite sequence. First comes the oppression, say, slavery. Once slavery is established, someone invents a racist idea to rationalize and protect it from criticism and abolition.

7. What are several examples of a racist idea?

Polygenesis: A cultural anthropological speculation that human groups arose separately and independently of one another. The result accounts for the different racial categories that appear to exist today. Asians, Africans, Europeans etc. are descendants of different “parents” and therefore fundamentally different kinds or species. Being fundamentally different they are comparable with one another, some becoming inferior.

Climate Theory: a variation of polygenesis that believes the warmer the climate, the more dark and culturally delayed the people. This theory ran into a snag when in 1577 travel writer George Best some of the Inuit people in northeastern Canada and realized that they were darker than the people living in the hotter south.

The Imbruting Theory: the diminishments of slavery or racial oppression “imbruted” African peoples damaging them beyond their ability to recover.

The Whiteness as Achievable Theory: held that Blacks were Whites who had lost their whiteness through some form of oppression. Whiteness, even lightening of dark skin, was possible through education, acculturation, and getting out of the sun.

The Biblical Curse Theory: Because the Hebrew Bible depicts humans as created by God and arising from Adam and Eve and later from Noah, the polygenesis idea is fundamentally non-biblical. A particularly Christian form of racism employs a tortured interpretation of the Genesis 9 story of Noah’s drunken condemnation of his son Ham or possibly Canaan. Basically, the Curse theory holds that African peoples are predestined to servitude.

The Black Retaliation Theory: Black resentment over the cruelties they’ve suffered has built up retaliatory pressure in the Black population, which they will unleash if given opportunity. Blacks need to always to be confined, monitored, and outgunned.

The Uplift Suasion Theory: This idea assigns blame for White racist attitudes on Blacks themselves. If Black people would only prove themselves to be cultured and ambitious Whites would approve, moderate their disdain, and a virtuous cycle of equality and tolerance would result. In the American Revolutionary period an enslaved Senegalese woman, Phyllis Wheatley proved herself to be a brilliant English language. Abolitionists paraded Wheatley around the country in an effort to demonstrate the potential of the African peoples. The racist idea here is that racial justice only lacked exemplary Blacks behaving like cultured Whites.

8. What can people do to move towards antiracism and a just society?

The answer here is simple: Remove the unjust structures. Today in Florida and other states a Jim Crow era holdover law deprives certain ex-offenders from voting either for the rest of their lives or at least for a long period. Kendi would say, “repeal the law.” Instead of trying to change people’s attitudes or identifying the racism which underlies such laws, simply ending the law is probably the best course.

Kendi makes clear that racist ideas follow rather than precede oppressive practices. Long after slavery was established in America and cotton exports had become the economic engine driving the entire economy, Southern novelists, clergy, and essayists began producing a vast pro-slavery literature. These books glorified slavery as a godly institution and the South as an exceptionally blessed civilization. This flurry of writing didn’t come before African captives were packed in sailing ships for the voyage to the New World. These ideas developed when the the first captives’s grandchildren worked the cotton fields of the American South. Racist ideas follow discrimination.

Abolishing the oppression—chattel slavery, Jim Crow, mass incarceration, or housing segregation–which engenders a need for racist ideas is the logical first step.

Says Kendi at the end of his book:

An antiracist America can only be guaranteed if principled antiracists are in power, and then antiracist policies become the law of the land, and then antiracist ideas become the common sense of the people, and then the antiracist common sense of the people holds those antiracist leaders and policies accountable.

A Final Thought

Kendi has shined a steady light on racist ideas’ subtlety and persistence through American history. What’s interesting about Kendi’s survey is that he brings to light how difficult it is to avoid some sense of Black inferiority. Lincoln did it. Thomas Jefferson did it. Virtually everybody, even those who labor to improve the lives of their Black neighbors, slip into some racist assumptions. Kendi himself credits the study he did in writing Stamped from the Beginning for exposing his own assimilationist racist ideas and enabling him not to become an anti-racist.

The difficult of avoiding racism, however, may be improving. In the last couple of decades, two related scientific developments have made it difficult for racist ideas to proliferate as they have in the past. These developments have been:

1) the sequencing of the human genome and

2) the growing consensus among cultural anthropologists that modern humans are of one species and share a common ancestry.

Put in the simplist way possible. We’re all of one family. Physical differences, such as facial features associated with African or Asian peoples, are recent adaptions to climate and living conditions. Much like the differences in clothing, the superficials in human appearance are far less indicative of fundamental differences than our parents have traditionally assumed.

Otherwise, people and groups of people are remarkably the same. As one scientist put it, there is more variation within a racial group than there is between racial groups. There are few absolute, immutable differences between people or between groups.

Kendi devotes a chapter, “99.9 Percent the Same,” to these developments.

Two scientific developments have made it exceedingly difficult for racist ideas to proliferate as they have in the past.

Christians can point to a development in biblical study that certifies that the Bible itself is an antiracist document. Within the realm of biblical interpretation, scholars know with certainty that the Bible, despite its antiquity, is free of any racialized construct of human society.

J. Daniel Hays book, From Every People and Nation: A Biblical Theology of Race (New Studies in Biblical Theology), is one example of an exhaustive survey of the Bible for any racist teachings or assumptions. Justifying slavery or the denigration of any racial group is a vestige of passé biblical interpretation and will never again gain traction in thoughtful churches, liberal or conservative. I believe that there’s a quiet ecumenical consensus that racist ideas are alien to the Christian thought world.

Reading Stamped from the Beginning is an excellent way of building a historical foundation for further study of race and racial justice. More importantly, it’s a great way to launch one’s adventure in becoming an antiracist.

You may also be interested in:

Through Victim’s Eyes: James Baldwin’s Vision of Racial Justice