Facing our War on Blackness: What We Must Do Now

Book Review of Katie Walker Grimes: Christ Divided: Antiblackness as Corporate Vice

I tell myself that I’ve traveled a long path looking for fair and peaceful relationships with people different from me. So has our country. Before the events of Charlottesville, Virginia in September 2017, I might have thought that racial attitudes have settled into a standstill for now. There are no truly new steps to take.What I didn’t expect was for a theologian and academic to shove me a good bit further up that path. About half-way through Katie Grimes just-released, Christ Divided, I had to admit that I’d never thought of Race in quite this way. I began to wonder if I was reading a watershed statement on racial justice.

I’m impressed with Grimes’ work on several counts. This is a fresh take. She’s unfreezing old habits of talking about race. She’s pulling out moral anthropology that, to my awareness, has not yet been put to work for racial justice. She is confident enough in her ideas to be blunt in rejecting those set forward by Protestant ethicist, Stanley Hauerwas, or Catholic race relations expert, Francis Cardinal George. She effortlessly sets aside nostrums like “colorblindness” or “White supremacy” as imprecise in their usefulness for eradicating this cancer that pervades the bones of White society.

Antiblackness Supremacy

Grimes central contribution here is to expose a deep unacknowledged evil; a hostility reserved particularly for people of African descent, which has reigned unchallenged for a long time in the White Way of Life. Oh, White Supremacy, which is Whites first over the brown races, marches on. But that term—White Supremacy–doesn’t admit to a specific victim. What Grimes has done is to demonstrate that the main game we’ve been playing is to make and keep Blacks as the victims. She has coined a term for this evil: antiblackness supremacy.

What makes Christ Divided compelling is that it demonstrates in history, in America, in church, that White dominant culture has reserved an exceptional disadvantage for people of the African diaspora. And this habit of forcing Blacks downward replays itself endlessly even when we want to deny that we have anything to do with it.

Transforming the Conversation on Race

Christ Divided is ambitious. I found myself comparing it to two, riveting books on race: Michelle Alexander’s, The New Jim Crow, and Isabel Wilkerson’s, Warmth of Other Suns. Alexander drags into the sunlight evidence of racial selectivity in the justice system which has landed so many African American men in prison. Wilkerson narrates how slavery’s hardships didn’t really end on January 1, 1863. Mutations of slavery retained slavery’s oppressive power over even ex-slaves who escaped the South for big cities in the North.

Grimes is attempting something yet more transformative. She wants not to reinforce my outlook on race, but to transform it. She wants to convince me that slavery lives on, not in the sense that the share cropping economy was similar in oppressiveness to chattel slavery, but in the sense that I’ve become addicted to the slave master’s life style of dominance, violence, social respectability, sense of innate superiority, and material gain. This “afterlife of slavery” has become habit for me and for my community. Habit continues without thought. Without thought it becomes simply part of being White.

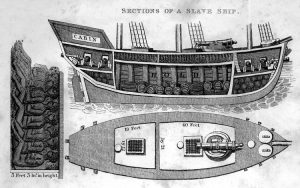

The Slave Trade

Christ Divided finds this insidious tendency for people to align themselves against Blacks through Western history, ever since the Slave Trade’s start in the 15th century. In those days, Old and New World civilizations bumped into one another and needed to sort out their own racial pecking order. Africans were loaded onto ships. Pilgrims sought refuge among Native Americans in the New World. European nations strove to sail exotic outposts and to load ships with more and more cargo. As winners and losers arose and declined in this period of exploration and trade, one group, African-descent peoples, fell victim to some kind of sinister process that predictably landed them on the bottom.

One example of this, typical of several in the book, comes out of Spain in the mid-fifteen hundreds. At that time, Spanish White Catholics clashed with Muslims and Jews over their alleged role in diluting Christian orthodoxy. This was the core struggle in the Spanish Inquisition. Less well-known is the fact that Spain had a small Black slave population that was Christian. Those Black Catholics possessed no polluting Jewish or Islamic blood or other religiously contaminating qualities. The Blacks should have not been of interest to the Inquisitors. Nevertheless, in Saville, a Spanish mob jeered at and assaulted a Black devotional group dedicated to Mary, as they processed through the streets of Seville. The unruly mob’s mentality must have been: “We see Blacks, Africans, slaves, they must not really be Christians. They are as odious to our society as Jews and Muslims. The mob’s irrationally betrays something else driving their antiblack attitudes when the official struggle was with the rival religions.

It is important to understand this subtlety: Jews and Muslims possessed their own religion and language. These factors made them more familiar in Spanish society than were Blacks—who were descended from Ham and deemed unconvertable. Accordingly, Jews and Muslims, who were in the logic of the time real religious threats, could and did recover socially. The seeming irreligion and African background of Blacks, however, locked them into low Caste status as slaves, criminals, and non-believers. In short: Black equals slave and slave equals criminal and non-believer. I linger over this detail in Spanish history, because it conforms to an insidious dynamic that in countless instances pushes Blacks, and only Blacks, to the bottom of society.

Threading through the book are retellings of this story with different details. In our own American context, most of us have observed that German, Irish, Asian, and Hispanic immigrants in this country began their American experience by facing suspicion by the locals. Immigrants have found it useful at least upon arrival, to settle in their own ethnic neighborhoods. They start poor. Despite the rough start, immigrants manage to assimilate. They figure out how to gain full social acceptance along with prosperity.

Blacks, on the other hand, tend not to assimilate. They remain disempowered, lack in social standing, end up much more incarcerated, isolated, and poor. Grimes credits this to the dynamic she has named “antiblackness” which is essentially an unconscious community habit which persists in putting Blacks at great disadvantage.

This disadvantage is rooted in a fascinating process, cast into a term coined by African American Literature and History expert, Saidiya Hartman. The term is, “the afterlife of slavery.” Here’s how slavery can have an afterlife. Chattel slavery roundly assaulted human beings, families, and communities. Slavery tore apart marriages, placed people in dependency, alienated workers from their labor, confined Black bodies to ghettoes, and was saturated with violence. Slavery also brought “benefits” to the slave master. The master got a false social uplift by being able to dominate someone. He was enriched by someone else’s labor, possessed a captive sexual partner, and could, all the while, feel magnanimous because someone depended on him to eat. To say that slavery has an afterlife is to say that the slave’s diminishments and the master’s benefits march on even after emancipation has taken away the whip and broken the chains.

I, for example, am an absent-minded driver. I make the same trip to my home day after day. Going home is muscle-memory. Even without trying to develop a habit there is one. I turn here, exit the interstate there, and get in the left-hand turn lane at this particular intersection. It always gets me home even when the radio blares and my mind is working on some other problem. But what if I want to stop at the grocery store on my way home? In my case, there’s a good chance that I’ll remember the grocery story just about the time I pull into my driveway. Habit is running the show.

Corporate Antiblackness

Anti-blackness is habituated behavior lodged in whole societies—White society. It’s a kind of muscle memory that we’re not thinking about or intending which lands us where it has always taken us instead of where we need to go. It is bodily. It resides in our organization of cities, schools, churches and even language.

Christ Divided’s second half focuses on the American Roman Catholic Church, not as interrupting antiblackness, but as infected itself with it. As in the early chapters, Grimes masterfully pulls in example after example from the history of the Church of the insidious workings of antiblackness even in the Body of Christ. The reader will find here plenty of instances of clergy benefiting from slaves, segregated masses, all-white parochial schools, and Black’s-only parishes.

What to Do?

It is in congregational setting that Grimes sees promise for meaningful push back. Her proposals are unsettling. What if, she suggests in the most refreshing of ideas, the typical “cultic” mass held in sanctuaries, was replaced by a real meal in prisons? People who might not otherwise eat together, recalling Jesus’ practice, would sit around a table and dine. The whole thing would be sanctified by a great prayer of thanksgiving, but an ordinary loaf would be broken and shared. It would be a meal. All of the gritty factors of implementing jail masses, like transportation of middle class parishioners downtown, would take on sacramental and transformative power.

What a time for a book of this caliber to become a part in America’s intensifying conversation about race! News commentators, this morning, were criticizing White House Chief of Staff, John Kelly’s remarks about failure to compromise as the Civil War’s cause. At the political Right’s dark extreme, armed men, dedicated to a vision of America as fatherland for European heritage people, launch websites and practice shooting on weekends. Video from recent Police shootings of unarmed Blacks has launched a controversial movement, Black Lives Matter. Katie Grimes has helped me to look at all of this with a new lens and the unnerving question: Am I yet a part of an enmity towards Africa’s children that I neither acknowledge nor even understand and that continues as insidiously, as destructively in 2017, as it did in the 15th century?