Why We Need to Study Slavery in America Now

As the 2020 election season warms up, the idea of providing reparations to American Blacks, most of whom are descendants of enslaved ancestors, is a hot item. Candidate Elizabeth Warren, an early supporter of a bill in Congress, which provides for reparations, is actually seeking more than just compensation. She wants to see a nationwide conversation about slavery in America.

Twenty years ago I would have yawned and responded, “Really? Haven’t we studied that subject to death?”

As with almost every political topic, I’ve changed my mind about slavery. It may be illegal, the Emancipation Proclamation and the 13th Amendment have insured that. Chattel slavery is technically gone.

But the value system which accompanied our enslaving of Africans since the 16th century continues with us like a poisonous miasma. So much of what we see today, from mass incarceration to the rise of White Nationalism is the natural offspring of slavery.

One critic of Elizabeth Warren’s proposal is Katie Pavlich, a Fox News contributor, who provoked loud outrage when she said on air:

They keep blaming America for the sin of slavery but the truth is, throughout human history, slavery existed, and America came along as the first country to end it within 150 years. And we get no credit for that to move forward and try to make good on that.

Katie Pavlich

Twitter mavens and media figures have thoroughly discredited Pavlich’s statement. But the fact that such thinking could reach a national audience alerts us to a widespread faulty understanding of our own history.

Elizabeth Warren’s desire for a nationwide reassessment of its slave tradition would bring a much-needed reset or our national self-awareness, and unburden our children from carrying forward a distorted—often intentionally—story of what really happened to Black Americans caught in the plantation economy and its aftermath.

Leaving aside the feasibility of reparations, here are three reasons why every American needs to study and re-think slavery.

1. It hasn’t been studied before.

Okay. That’s obviously an overstatement.

Every American adult has spent time pouring over the big American History textbook at some point or several points in high school. The problem with the history of the 19th century South and reconstruction is that these topics have been massively and obviously whitewashed.

Historian Eric Foner begins his recent, magisterial history of Reconstruction with these bracing words:

But no part of the American experience has, in the last twenty-five years, seen a broadly accepted point of view so completely overturned as Reconstruction—the violent, dramatic, and still controversial era that followed the Civil War.[1]

Eric Foner

To put it bluntly: What we’ve learned about the Civil War’s aftermath is simply wrong and needs revision.

Anyone today who is willing to look can see the blatant mendacity of the effort to sanitize what really happened on the plantations and in the Southern states following the Civil War. One simply needs to read one of the many plantation novels that were popular during the 19th century.

I read and reviewed The Reverend William Warren’s 1864 novel, Nellie Norton last year. Nelly Norton is a pleasant enough read. It’s a love story. It has been unavailable for many of the years since its publication just before the end of the Civil War. It is now digitized and posted on the internet.

The novel is also ugly propaganda that is so crude that a junior high student could see through its deceit. It dares to say, at the very moment when emancipated slaves were joining the ranks of Union Army units, that slavery was the heart of the Bible. It insists that slavery as practiced in the American South represents the zenith of human civilization. Nelly Norton claims in eerily Christological language that the South, will rise again and be enthroned on all of nations’ praises.

No kidding. Someone was believing this stuff.

Nellie Norton is but a drop in an ocean of Southern literary and artistic efforts to defending slavery and erect a mythical edifice that overshadowed the gritty realities of everyday life in the Confederacy.

There’s a name for this propaganda effort. It’s called the Lost Cause.

To those of us who haven’t been paying attention to the developments in American history since the turn of the millennium may be carrying a “Gone with the Wind” image of Southern life. We may be thinking that chattel slavery ended so long ago that to keep flogging it is a pathetic effort by liberals to create an issue where none exists. But the groundswell of work in American history suggests that we need to take another look at what happened in our country through the 19th century.

But my first point is that it’s the myth we’ve studied and memorized. Now it’s time to look at what really happened.

2. It’s still with us

Americans are freshly interested in racism and social justice. I’m in a book club that is focusing on racism and there is a stream of inquirers who, without efforts to recruit, want to join.

Google Trends has logged a sharp increase in web searches on topics such as discrimination and identity relations. If you look at the search volumes for terms like “bigotry,” “white privilege,” “racism definition,” “xenophobia,” “ageist” and “misogyny,” you’ll see a sustained increase in the last six to seven years.

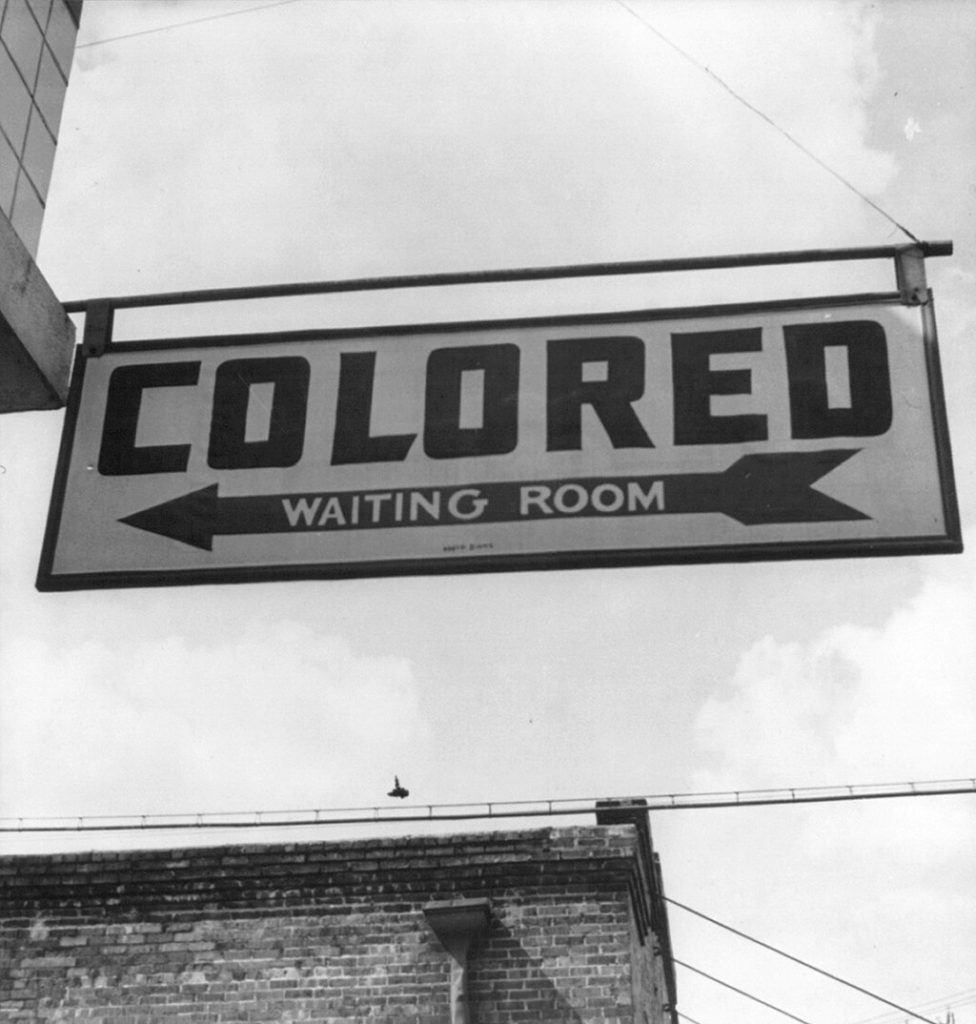

It would be convenient to think that once the Emancipation Proclamation was issued in 1863 that the boil had been lanced and that healing would follow. What actually happened was that Blacks were re-enslaved through Black Laws and later, Jim Crow. What has followed for African Americans was an “afterlife” of slavery. That term was coined by Saidiya Hartman after she traveled to Africa to retrace the steps her forebears were forced to take as captives who would be transported to the New World, sold, and forced into labor.

Hartman’s journey brought her into a sobering realization that the conditions that her ancestors endured—the loss of a fulfilling life, limited access to healthcare and education, premature death, incarceration, and impoverishment—continued on in the experience of the Black community. They continued in her own life as an African American woman. Hartman reported that she wasn’t so much learning about the slave trade as she was learning about herself.

The whips and manacles are gone. But the spirit of slavery still haunts America. The time has come to face it, name it, and put it behind.

3. We live in a time blessed by fresh resources to look at our past.

Two scientific developments in the last 20 years make racism—the belief that any human group is superior or inferior—untenable. The first is the “Out of Africa” hypothesis, which holds that Homo sapiens originated in East Africa and, despite minimal interbreeding with other archaic species which belonged the genus Homo, are the only species of human that is not extinct. Anthropologists generally agree with this scheme. In turn, there is a consensus among anthropologists that only one species of human being exists. Put simply, we’re all from the same ancestor.

The reason this is important is that it undercuts the the racist’s most pernicious assumption, namely that different races are different species of humans.

The second development comes with the sequencing of the human genome, which reaches the same conclusion, namely that there is more genetic variation within racial groups than across racial lines.

All of this leads to a widely used expression. Race is a “social construct.” It is a way of looking at people, which is entirely the product of the human imagination and not rooted in any hard evidence. Race as a way of categorizing people is far closer to the distinction between blonds and brunettes than that of Blue Birds and Cardinals.

We really didn’t need the advanced techniques of anthropology or genetics to realize that race and racism are fictive cultural inventions. If we look at the history of science and literature, it is obvious that racist ideas are generated by society’s best minds as a justification of economic injustice. In the antebellum South for example scientists, clergy, and creative writers began concocting ideas about enslaved Africans that served to justify the Plantation system, which at once was so profitable and so maligned by Northern abolitionists.

Hence the need for a fresh study of slavery.

Actually, slavery and racism have been under intense study for several years. This interest mirrors the rise of White Nationalism. This pattern of progress and regress has long been part of the history of race in America. We’re always going forward and backwards at the same time. The Abolitionist movement was answered by the Plantation Novel. Civil Rights Movement was answered by mass incarceration. And so on.

The question is which side will we be on.

Now I’m going to read Edward Baptist’s, The Half has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism, a great way to start what we all must do.

[1] Foner, Eric. Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877 (Perennial Classics) (Kindle Locations 104-106). HarperCollins. Kindle Edition.