Nellie Norton, Slavery, and the Weaponized Bible

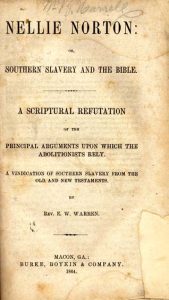

I‘m too embarrassed to share here how much time I’ve spent reading and now writing about Nellie Norton an out-of-print, pro-slavery novel. By any standard, Nellie Norton is junk literature. It’s racist propaganda. It has a thin plot that is designed to make racist ideas palatable and the slavery-based American South seem enlightened. The book mangles the Bible’s meaning. And its author lies shamelessly about the South and about enslaved people.

I’m not familiar enough with pre-Civil War Southern writings to know what Nellie Norton‘s influence has been. But it could not be good. I’m guessing that novels such as this one stalled this nation’s recovery from the evils of slavery. Because of Nellie Norton and books like it, the stain of racism on the American character is a bit more indelible.

Nellie Norton is an evil piece of work. Yet the more I read the more obnoxiously fascinating it was for me. It’s the story of a young Northern woman, Nellie, who is visiting her uncle, a plantation owner. The story’s action takes place during Civil War hostilities, though the war appears to make little impact on the characters. Nellie is a lovely person, intelligent, open-minded, and pious. Ultimately, she falls in love with and marries one of the characters a neighbor of Mr. Thompson. This love affair corresponds with her being won over to the superiority of the southern way of life.

The make-believe world of Mr. Thompson’s plantation is a serene, happy place. It’s pastoral and genteel. The book’s characters spend their afternoons in the parlor absorbed in pious conversations about the Southern way of life. These discussions carry the book’s message, namely that slave-keeping in the South is an ideal form of society.

The Reverend Pratt, the Yankee preacher, is visiting Georgia on doctor’s orders. He is the author’s embodiment of degenerate Northern intellect. Pratt’s sickness is a metaphor for Northern pathologies. Implied is the idea that the North is sickening; the South, therapeutic.

Even the book’s decorous prose is fragrant and feels noble.

Reading this book helped me understand more about Southern culture. I lived in Georgia for fourteen years. I’m just beginning to understand that experience.

Warren’s story places Southern rural aristocracy on display. Without embarrassment, he celebrates White male privilege, anti-intellectualism, legalistic religion, regional chauvinism, and Victorian manners. Of course, the world that Nellie Norton glorifies has passed from history. But vestiges of Old South values live on today.

Nellie Norton, belongs on that large pile of B-list fictional works that romanticize what became the Confederacy, particularly its institution of slavery. The Antebellum South produced more racist literature than any other place in history. Virtually all Southern fiction, together with much non-fiction, defended slavery and insisted on the superiority of all things Southern.

Southern writers didn’t always glorify slavery. Before 1831, when William Lloyd Garrison’s launched his widely-circulated abolitionist newspaper, “The Liberator,” Southern intellectuals defended slavery as a necessary evil. After 1831 and the intensification of abolitionist fervor, Southerners began to insist that slavery was a social positive. Pro-slavery apologists reasoned that the South was a superior civilization because chattel slavery was at its center. These writers went on to insist that the North was a swamp of decaying cities, warped ideas (Transcendentalism, Women’s Rights, Catholicism, Mormonism), a declining work ethic, economic stagnation, and religious apostasy. The novel, Nellie Norton, published in 1864 by attorney-turned-Baptist minister, Ebenezer Warren, belongs to the category of late proslavery, pro-Southern writings.

If Nellie Norton had been made into a movie it could have used the same set as “Gone with the Wind.” All of the Old South keepsakes make their appearance in the story—chivalrous gentlemen, hoop-skirted ladies, happy and comically inept slaves, evangelical piety, rural wholesomeness, and even good-weather.

Missing from the novel is the fact of a raging Civil War. As Rev. Warren pens his story of Mr. Thompson, the Reverend Pratt, Nellie, and her mother wasting whole afternoons discussing the Old Testament’s institution of slavery, a devastating war is destroying the region’s economy. Lincoln has issued the Emancipation Proclamation. Slaves are stealing away from cotton fields to find and assist Union Army units. The Battle of Gettysburg, which will seal the Confederacy’s fate, is an accomplished fact, or will be in mere weeks. As Warren writes, General Sherman is getting ready to carve a scar through Warren’s plantation paradise.

Nellie Norton was written for Reconstruction-era Southerners in order to pronounce absolution over the cruelty of slavery by finding it to be encouraged in Scripture and humane in practice.

The reader must wait until the end of the story before the author acknowledges the war. Warren depicts what appears to be the Bull Run rout on the book’s final pages. My best guess is that action of the novel unfolds in 1860, the author writes in 1862 or 1863, and publishes in 1864. Thus Warren writes toward the end of hostilities, knowing what the very civilization he is glorifying has collapsed.

Who was the intended reader of Nellie Norton? What conclusion was he or she to reach? Had the book been published 100 years earlier as the labor-intense cotton boom was beginning, it would certainly be read as a tract that gave moral sanction to the use of slaves. But coming at the end of that era makes the novel’s appearance, together with the publication of scores of similar books, a real puzzle.

Reading 209 pages of Warren’s ostentatious prose might seem unbearably tedious. It was indeed tedious in the over-long discourses on biblical passages. But the book’s sections that carried the plot and what I’ll call “sociological arguments” supporting slavery were tolerable. Ebenezer Warren has produced a readable example of a pernicious genre. There’s so much to criticize about this book. But I’ll grant reluctantly that Warren’s prose is elegant enough and the evidences of his learning are plentiful enough justify the conclusion that he was a thought leader in his society.

Sounding smart was actually one of the book’s goals. Warren wishes to push back against the shaming effect of abolitionist diatribes and growing European condemnation of the plantation system. So much of the book’s message might be summarized as “we’re not as backward in the South as you arrogant intellectuals think we are.”

While I admire Rev. Warren’s story-telling, his proof-texting exegesis of scriptural verses (or partial verses) is tiresome. The author tweezers fragments of verbiage out the biblical text, declares that they are infallible revelation, pairs them with other verses, and draws conclusions that would surprise even the ancient authors. Mr. Thompson’s parlor discourses are examples of a deductive interpretive approach, which reads the Bible as one would read the rules to Parcheesi.

As a result, these arguments failed to move me. My attitude towards slavery didn’t budge even after two hundred pages of careful biblical argumentation. Add to the legalistic bible interpretation the author’s generalizations about Africa’s desolation and the nature of Black peoples, and one understands why Nellie Norton is no longer read, nor deserves to be.

This novel strikes me as the work of a humiliated society. How painful it must have been to have one’s way of life vilified by an army of abolitionists, women’s rights partisans, non-Protestant Christians, and Yankee intellectuals. The book must have satisfied its original readers’ yearning to retaliate: “Yeah, you think you’re so smart! We’re smarter. And we’re richer. And we’re better Christians.”

The thought that the author was too smart for what he was writing kept floating through my imagination. I wondered if Warren really believed that the Bible was “slavery-centered.” Or was he arguing like the defense lawyer who knows his client pulled the trigger, but who nevertheless needs spirited representation? Warren was an attorney before his desire to “win souls” led him to the pulpit.

What this Book is About

Here’s my best answer to the question of Nellie Norton‘s audience and purpose: The novel was written for Reconstruction-era Southerners in order to pronounce absolution over slavery’s horrors. It achieves this by finding chattel slavery to be humane in practice and encouraged in Scripture. Nellie Norton was written for Reconstruction-era Southerners in order to pronounce absolution over slavery’s cruelty by finding it to be encouraged in Scripture and humane in practice. Warren further seeks to salve his society’s conscience with the wistful prediction that the vanquished Southern way of life will someday live again and become, slaves and all, a beacon for all of humanity.

This thesis sounds even to me like overreach especially the part about the South’s future glorification. But Rev. Warren states it explicitly late in the book:

Had we effected [sic] a separation, moral, religious, social and political, twenty-five years ago, the South would now have been the greatest nation in the world, as it is destined to be at some future day, if we are but true to our God and to ourselves. When the last link that binds us to the North is broken…and slavery and the South left to the destiny marked out for them by the Hand which guides the universe, her career, under Providence, will revolutionize the morbid sensibilities of the world on the moral validity of slavery. The world is wrong, and the South must set it right; the world is in error and is dependent upon the South for ‘the truth, the whole truth,’ unmixed with the alloy of mistaken and misguided humanity. When left to herself, her prosperity will be without a parallel. Her moral and religious, her social and educational interest will outstrip, in their advancement, any national progress known [sic] to history. She possesses greater undeveloped resources of mind and material than any nation upon earth.

Nellie Norton‘s author develops two common racist ideas in his effort to sanitize slavery and the Southern way of life.

- The idea that slavery is the best of all possible conditions for captive Africans.

- The idea that God has cursed African-descent peoples to perpetual servitude as taught in the Old Testament.

I. The Best of All Possible Conditions

A story threads through the book. It provides the frame for several parlor talks, which taken together, lay out a thoroughgoing defense of slavery. The protagonist is a young woman, Nellie Norton, from the North. She and her mother are visiting her uncle, Mr. Thompson, a planter, and slave-owner. Nellie has heard of slavery’s evils, but wishes to see slaves in the flesh, discuss slavery, and make up her own mind about the South.

Nellie’s pastor and brainwashed abolitionist, Dr. Pratt, is also traveling in the South to improve his health. He becomes a house guest of the Thompson’s. The novel portrays Dr. Pratt as a disagreeable person. He stubbornly clings to abolitionist propaganda in the face of abundant evidence for slavery’s godliness, which is provided by Mr. Thompson. The story depicts Pratt as repeatedly being out-debated by the commanding learning of layperson, Mr. Thompson. He’s also shown to be a coward and scoundrel, despite his clergy vocation.

The character list includes a collection of slaves with names like “Uncle Jesse,” “Jim,” and “Aunt Fanny.” Finally, a neighboring plantation owner and young bachelor, Mr. Mortimer, is on hand and becomes the lover and husband to Nellie by book’s end. Nellie’s native common sense and

The slaves’ condition, Mr. Thompson confidently explains, is the most abundant life possible for these the otherwise cursed children of Ham.

basic goodness put her in a position to see the godliness of Mr. Thompson’s arguments and the merriment of his slaves. By book’s end, she wishes to live out her life with the Southern gentleman and planter, Mr. Mortimer.

The uncomplicated story consists mostly of Mr. Thompson’s discourses from the Bible alternated with observations of the slaves. In one maudlin episode, Mrs. Thompson is sickened to the point of death with pneumonia. Mr. Thompson’s slaves are grief-struck at the prospect of losing their “mistis.” Mr. Thompson permits the crowd of slaves to gather around Mrs. Thompson’s bed in order to pray for her. Predictably, she recovers.

Of course, a fictional account cannot prove that slaves are happy and well-treated, but the story depicts them as happy, spiritual, and childlike. Nellie, her mother, and Pratt are astounded at what they witness again and again in those who apparently are in happy captivity. Their condition, Mr. Thompson confidently explains is the most abundant life possible for these the otherwise cursed children of Ham. Emancipation and deliverance into the freedman’s existence, such as that endured in the North, would only diminish the life of these lovable servants.

The reader wonders whether the book’s author was aware of slavery’s cruelty, which drove thousands of captives to flee their bondage once the war and Lincoln’s Emancipation disrupted plantation operations. After several episodes where Mr. Thompson’s slaves demonstrate their faith, their singing of hymns, their love for the Thompsons, and their cartoonish interpretation of biblical stories, Nellie is able to declare that she has been lied to in the North and that she has come to have a high respect for what was being done for the African race in the deep South.

II. Cursed to Perpetual Servitude

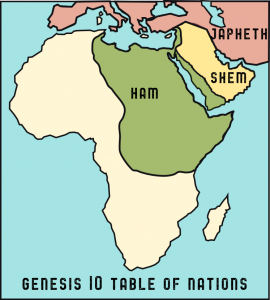

Much of the novel is devoted to Mr. Thompson’s lawyerly interpretation of the scripture’s “institution of slavery.” Warren is putting forth the Curse of Ham (Genesis 9) racist idea, which may have been the South’s most prominent argument for slavery. The curse of Ham takes place in Genesis’ primeval history as part of the Noah’s Ark story. Following the Flood, Noah and his family leave the Ark and re-establish humanity. The strange story tells how Noah, drunk and naked, is seen by his son Ham. Later Noah is discretely covered by his other two sons, Shem and Japheth. The story’s meaning for today is murky. We’re not exactly certain what is objectionable about Ham seeing his father’s nakedness.

Upon awakening, the hung-over Noah doesn’t actually curse his son Ham, but Ham’s son, Canaan. The curse’s substance is that Canaan is consigned to servitude to his uncles, Shem and Japeth. Technically, there is no explicit curse of Ham. And God doesn’t do the cursing. Without filling this essay with a speculative interpretation, we can summarize the interpretation of the episode by saying that there was probably some ancient negativity toward the Canaanite tribes which finds cryptic expression here. A satisfying interpretation of this text may never be forthcoming.

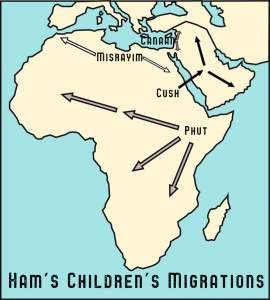

That said, Rev. Warren, states that Ham’s children (Misraim, Put, Cush, and Canaan), who migrated into Africa and much of the Middle East, were all consigned to slavery. The Canaanite tribes settled in Palestine. The curse theory isn’t precise enough to pin down exactly who carries the curse. Canaan never really goes into Africa.

Neither does the Curse of Ham theory follow Ham’s progeny, whose movements and territories are revealed in the Bible. Their continued status as cursed people never appears again in the Bible. Canaanites, Kushites, Phutites, and Misriam migrate into non-Hamitic lands and marry the descendants of Shem and Japheth.

For example, Abraham, the father of all the faithful, has a baby with Hagar, his wife’s Egyptian slave. Egyptians owe their origin, biblically speaking, to Misriam, one of Ham’s sons. So Ishmael is a 50-50 racial mix of Shem and Ham. Does the curse cover him? If so, that conflicts with Genesis 17.20, which states that he and his mother, Hagar enjoy a special and permanent blessing by God. Arabian peoples claim him as their patriarch.

The story of intermarriage and ethnic intermixing is repeated several times in the Bible. Jacob goes back to Shem territory to find wives. That fits the script. But brother, Esau, dates the local Canaanite girls. What’s the status of Esau’s kids? Joseph, Jacob’s youngest son ends up in Egypt and the Pharaoh gives him an Egyptian wife, Asenath, who bears him two sons, Manasseh and Ephraim. These two, who are numbered among the twelve patriarchs, are half Hamitic. If the first of Jacob’s sons, Joseph, takes a Hamitic wife, we can only guess at the amount of racial intermixing that would take place over the span of 400 years while the Hebrews were in Egypt before they were released through the Exodus.

I’m amazed that by the time Moses came along that his people had any family identity at all. And speaking of Moses, he married Zipporah, a descendant of Ishmael. (Exodus 2.21) And as if all the intermarriage wasn’t enough, there is one obscure verse in Exodus (Ex 12.38) that indicates that a mixed multitude accompanied the Israelites out of Egypt. These disaffected people later also came to be identified with Israel when they and their children were circumcised and participated in the Passover celebration.

A humanity divided into favored and cursed racial groups is not a biblical idea.

Here’s my point. Even if we grant that there is a curse of Ham/Canaan, movements of people and intermarriage in the biblical story obscure who exactly retains the curse. It’s not even clear in the ninth chapter of Genesis whether it is Canaan or his father, Ham is cursed.

If one thinks of the world of the Bible in general, there really is no development of a theme of dark-faced people being destined to a subservient existence. A humanity divided into favored and cursed racial groups is not a biblical idea. And lacking any development in the Old or New Testaments, it is implausible that suddenly in 19th-century American cotton fields God’s dormant intention for Ham’s descendants should come to fruition. And we haven’t even touched on the extent that enslaved women in the New World were raped by White men and bore children by their captors. Warren shows no awareness of these challenges.

The Institution of Slavery

Warren is aware that the Genesis 9 curse does not give warrant for Bible readers to actually set up a system of slavery. It merely identifies who the slaves are to be, namely Ham’s children. The command to set up a slave-based society, Warren finds in Leviticus 25.44-46. This text is embedded in one of the Bible’s most progressive teachings on debt slavery. Basically, Leviticus 25 limits the Bronze Age practice of enslaving debtors and their families. Every seven years such debts are forgiven and those in debt bondage are released free and clear. Such a provision is unique in the ancient world. It stakes out Israel’s territory for a special practice of economic justice. In the verses mentioned, the text acknowledges that slavery is practiced in the world around and that while Israelites may not enslave their brothers they may take as slaves people from outside their territory.

While moderns gasp at the stonings, holy war, and harsh punishments in the Bible’s first 5 books, it is important to remember that the Pentateuch put the organization of Israel’s society far in advance of the kingdoms that surrounded it.

The King James rendering of these three verses can be construed as a command.

44 Both thy bondmen and thy bondmaids, which thou shalt have, shall be of the heathen that are round about you; of them shall ye buy bondmen and bondmaids.

45 Moreover of the children of the strangers that do sojourn among you, of them shall ye buy, and of their families that are with you, which they begat in your land: and they shall be your possession.

46 And ye shall take them as an inheritance for your children after you, to inherit them for a possession; they shall be your bondmen forever: but over your brethren the children of Israel, ye shall not rule one over another with rigor.

Every other translation of Leviticus 25.44-46 renders the commanding shall in these verses with the permissive may. To paraphrase: “If you must have slaves, take them from someone besides your fellow citizens.”

Ebenezer Warren insists that this single verse establishes a holy imperative to keep slaves. He then fuses this requirement with the Curse of Ham, which supposedly identifies the tribes from which the slaves will be drawn and suddenly the Bible is a proslavery book. Warren presses on to state that failing to keep African slaves is to fail to take the Bible seriously. Warren insists that abolitionists, some of whom were Evangelicals and Quakers, had strayed into apostasy because they based their antislavery on biblical principles rather than on a tortured reading of a few verses.

My thesis here is that Nellie Norton soothes the shame of a society that has gotten rich through the stolen toil of generations of Africans. It does this by piecing together unrelated biblical verses, plucked from context, in archaic translation, and then argues page after page for the most contrived conclusion. To believe what Warren is arguing is to be desperate to believe it. It’s like the desperation of the terminal cancer patient who clings to some bizarre therapy advocated by a bearded holy man.

The New Testament and Slavery

The book’s proslavery interpretation of a couple of the Apostle Paul’s remarks is no less contorted and further reveals the desperation to employ Scripture in the service of a dying way of life. I’m not going to explore the handful of verses in Paul’s letters that plausibly could be seen as normalizing slavery. I’m going to look more globally at how Nellie Norton exploits the subtleties of the New Testament spirituality to make a hit-and-run argument that chattel slavery is okay. First of all, the great majority of Paul’s uses of the cognates of doulos (slave) are to explore the idea of slavery as a spiritual condition. He sees the Christian life as a kind of spiritual slavery to God or God’s cause. For example, in II Corinthians 4.5 Paul describes himself as a slave to the Christians in Corinth. More often, Paul describes discipleship with the metaphor of slavery to God. The Philippian letter, for example, starts out: “Paul and Timothy, slaves of Jesus Christ…” (Philippians 1.1). The opposite condition from slavery to Christ and the Gospel is slavery to sin (Romans 6.20) or people’s opinions (I Corinthians 7.23).

There are a handful of Pauline passages where the apostle speaks uses doulos to refer to actual captives who are locked in service to actual masters. While there is a debate on this subject, the Roman Empire had a vast population of enslaved people, as many as 25% according to one study.

Significantly, the same study indicates that Roman slaves were not usually African. Slavery, in other words, was a social norm and the tiny Christian movement held vision of human liberation that was grander than emancipation from slavery. In other words, the time to end slavery or the Roman Empire had not come.

This explains why Paul counsels Christian converts and their masters alike to exercise their new lives in Christ within the context of their social position. Paul gives similar advice to Christian converts who were married to unconverted spouses. “Don’t get divorced,” Paul counsels. Stay in your social situation and God will bless you. This is not to say that the spouse’s non-believing status is a Christian ideal. It is to say that God works in and through the current circumstance.

It’s worth mentioning that ending earthly slavery was an inherently Christian idea, which begins to gain popularity shortly after Constantine’s legalization of Christianity.

Slave or Servant?

Here’s how Nellie Norton upends all of this. Deep into the story, the characters gather in Mr. Thompson’s parlor for another lecture from the Bible. This conversation is the first of the group’s examination of the New Testament for its support of slavery. Nellie, her mother, Mr. Thompson, Mr. Mortimer, and the hapless Yankee preacher, Dr. Pratt gather. The tea is poured and Mr. Thompson, from memory, clears his throat.

There happens to be a Greek New Testament within reach, evidently a regular fixture in antebellum parlors. Thompson instructs his young neighbor, Mortimer, to pick up the New Testament. Nellie flushes with excitement as her beloved is shown to be familiar with Greek. I’m guessing that a lazy reader of Nellie Norton is thinking, “Wow, this is real scholarship. It even explores the original Greek.”

Dr. Pratt, the Northern Preacher, has also been trained in the Biblical languages, but as the reader has come to expect, he’s about to be humiliated once again by these Southern (male) Bible mavens.

The conversation turns to one word, doulos, whose English equivalent is slave. Since the Reformation, for reasons that I won’t take time to explore, most Bible translators have used servant to translate doulos. Like swatting the fly with a sledgehammer, Thompson proves to the point of tedium, dropping the names of every living Bible commentator and lexicon editor (Liddell and Scott, Grove, Alford, Hodge, Bloomfield, Trench, Stephens, Smith, MacKnight, Donnegan, Conybeare, Howson, Kendrick, and Hacket), proving with devastating conclusiveness that doulos is most accurately translated slave.

The point here, Mr. Thompson’s strategy, is to be sure that when the group’s attention comes to focus on Paul or Peter’s instructions for slaves to obey their masters (Ephesians 6.5-9, Colossians 3.22, I Peter 2.18-20), that the verse is understood as normalizing slavery. This is the effect: “Paul, speaking for God, says slaves ‘obey your masters.’ Implied in this instruction is the legitimate existence of slavery. The New Testament isn’t talking about hired servants but slaves. If Paul wanted to condemn slavery he would have done so explicitly. But in keeping with the institution of slavery in the Old Testament, he is giving instructions to slaves who find themselves within that institution.”

I am prepared to assert that the author himself knew he was deceiving his reader.

Anyone familiar with biblical languages easily sees through the veneer of great learning here. To come up with the root words in Greek and consult dictionary definitions requires one day of training in the Greek alphabet—a level that a college fraternity participant would have. This discussion of doulos, by the way, is Nelly Norton‘s most sophisticated examination of the biblical text. Nowhere in Nellie Norton is there a fragment of understanding of any Hebrew. Neither is there any translation of whole Greek sentences, nor any reference to the narrative context or theology of any text cited. Nevertheless, Nellie squeals in awe of Mr. Thompson’s vast erudition upon hearing him rattle off secondary sources confirming an unexceptional translation of a common Greek word. Hearing her uncle’s incisive biblical insight, Nellie moves forthwith to become a slave owner’s wife.

Warren mangles one biblical text so completely that I am prepared to state that he himself knew he was deceiving his reader. A word of overview: Thompson has reached the zenith of his argument for slavery and the Southern way of life. He now insists that succession–the departure of 13 states from the Union–is supported by God. Warren, through the monologues of Mr. Thompson, directs the reader’s attention to four words from I Timothy,“…from such withdraw thyself.” These words appear to be the culmination of of Paul’s instructions in I Timothy 6.1-5, which is printed in the text of the novel. There are three glaring weaknesses in Warren’s interpretation of this text. First, he gives no citation of chapter or verse. This is a subtle trick that makes it difficult for the average reader to consult the actual text and context in a Bible.

This detail that conceals the second deception, namely that Warren omits nearly 2 whole verses or 37 words in his quotation of the passage in stream of the novel’s story. (The omitted words are lined out in the text below.)

Let as many servants as are under the yoke count their own masters worthy of all honour, that the name of God and his doctrine be not blasphemed.

2And they that have believing masters, let them not despise them, because they are brethren; but rather do them service, because they are faithful and beloved, partakers of the benefit. These things teach and exhort.

3If any man teach otherwise, and consent not to wholesome words, even the words of our Lord Jesus Christ, and to the doctrine which is according to godliness;

4He is proud, knowing nothing, but doting about questions and strifes of words, whereof cometh envy, strife, railings, evil surmisings,

5Perverse disputings of men of corrupt minds, and destitute of the truth, supposing that gain is godliness: from such withdraw thyself.

Again, an exhaustive study of this text is beyond what I’m trying to do in this essay. That said, I consulted Eugene Peterson’s paraphrase of this text in his “Message” Bible. I think that if this text provides warrant for the succession of 13 states, it would certainly be clear in another rendering of this passage. Peterson presents these verses this way.

1-2 Whoever is a slave must make the best of it, giving respect to his master so that outsiders don’t blame God and our teaching for his behavior. Slaves with Christian masters all the more so—their masters are really their beloved brothers! The Lust for Money 2-5 These are the things I want you to teach and preach. If you have leaders there who teach otherwise, who refuse the solid words of our Master Jesus and this godly instruction, tag them for what they are: ignorant windbags who infect the air with germs of envy, controversy, bad-mouthing, suspicious rumors. Eventually, there’s an epidemic of backstabbing, and truth is but a distant memory. They think religion is a way to make a fast buck.

Obviously, it would surprise the Apostle Paul if he realized that one of his personal letters to Timothy was being used to justify the sundering of a huge nation nearly two thousand years in the future.

The final weakness of this argument, one that Warren himself probably didn’t know, is that the four words, “from such withdraw thyself,” are a textual variant that do not appear in the most reliable ancient manuscripts of the New Testaments. Admittedly, the King James Version of the Bible, dating back to 1611, which Ebenezer was using, carries the four words in question. As it turns out a complete and authoritative manuscript, namely the Codex Sinaiticus (א) that Tischendorf discovered in the St. Catherine monastery on Mount Sinai in 1844 was just coming to the attention to biblical scholars. It, together with other manuscript discoveries in the 19th century, provides substantial confidence that these words are likely not authentic. As a result, most contemporary translations don’t even have them.

That fact that Warren included in his novel this laughably contrived justification of Southern succession reveals the degree he is willing to stretch the plain sense of the Bible’s message in order to make his points.

Racist Ideas

In the prologue of Ibram Kindi’s, Stamped from the Beginning, the author reveals several patterns that emerge in the thinking of some of the wisest scholars, which result in the continued denigration and oppression of African descent peoples. Racist ideas come along after, rather than before, the oppression of Blacks, after slavery, Jim Crow, or mass incarceration has become a fixture in society.

Ebenezer Warren knew slavery’s brutality, he knew that the South was ruined, and he knew that the Bible was no pro-slavery book. Yet he scribbled away as the war raged around him. Most regretably, he turned the Old and New Testaments into a weapon against one large segment of God’s people.

And these ideas are cooked up by a society’s elites rather than common people. They serve to deflect responsibility for racial oppression away from the enslavers and towards Blacks and others.

Ebenezer Warren knew slavery’s brutality, he realized that the developed world had moved on from forcing people to work for no pay, he knew that the South was ruined, and he knew that the Bible was no proslavery book. But he scribbled away as the war raged around him. He invented smiling and singing Blacks, while real slaves were stealing away from their captivity. And most regretably, he weaponized the Old and New Testaments against one large segment of God’s people.

Finally, Warren placed on fictional Nellie’s lips high praise for all things Southern. He concocted a buffoon in Dr. Pratt, the grumpy abolitionist. He denigrated in the broadest of generalities the societies of the African continent. All of this was done to cleanse his reader’s memories. They weren’t going to open their Bibles and use their own heads to evaluate what they read in Nellie Norton. They weren’t going to laugh out loud at Nellie’s gullibility. Warren’s readers were simply going to take a cheap assurance of forgiveness and march on stubbornly as if nothing needed to be regretted or changed.