How Christianity Lost James Baldwin

I’m just coming to James Baldwin. I saw the documentary, “I’m Not Your Negro” and found it bristling with insight and heart. I moved on to read, Go Tell it on the Mountain. Pulitzer Prize journalist, Chris Hedges, lists Baldwin and Orwell as his favorite authors. That, for me, is a motivating endorsement. I decided to write this review as I became more engaged with this book. In the course of preparing this post, I read “Letter from a Region in My Mind,” which is half of Baldwin’s book, The Fire Next Time. I read that essay for the same reason I used to look up the answers to algebra problems in the back of the textbook. I wanted to make sure I was on the right track. I wanted my growing convictions about Go Tell it on the Mountain to be aligned with Baldwin’s mature assessment of religion. (to read more on “Letter From a Region in My Mind” click here.)

What It’s Like to Read this Book

This, Baldwin’s first novel, is deceptively sophisticated. The reading level, according to an online readability tester, puts the novel at a 12-year-old reading level. As I read the book, I realized that the author has hidden biblical allusions and pinprick pokes at church life that slipped by me on my first run through. As I dug deeper and deeper into this book, I wondered if I would have understood it even early in my ministry.

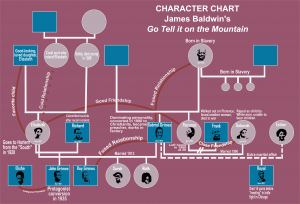

It helped for me to know ahead of time something that the author doesn’t explicitly state in the novel. James Baldwin eventually left the Church. Go Tell it on the Mountain gives the multi-generation story of why he walked out. I read the book a second, and then a third, time. In order to grasp what Baldwin was saying, I kept my own running commentary and developed a genogram, which charted who was related to whom. Though a 12 year old can read these words, I needed to spend a good deal of structured time in order to navigate its flashback laden, narrative path.

What the Book is About

The book’s protagonist, John Grimes, resembles Baldwin himself. Both are young, Black, Harlem-born, stepsons of abusive preacher fathers. As I became adept in finding my way around in John Grime’s family, I realized that I was learning how Christianity, or more precisely, how church, married to family dysfunction, could become a despotic force that damaged the lives of each of the book’s characters.

Before I read Go Tell it on the Mountain, I thought that I would be reading about race. Of course, race’s cruelty envelops the story, much as a theater encloses the drama played out on the stage. Baldwin’s project, however, is to show how a Black extended family, spanning three generations, can turn on itself the very elements of its cruel predicament and wind up under a new layer of bondage, namely the bondage of family-married-to-religion.

The story moves back and forth through the generations, dwelling in turn on John, Florence, Gabriel, Deborah, Elizabeth and others. These flashbacks explore each character’s struggles in sufficient depth to reveal how religion, usually in restrained ways, aggravates their lives’ tragedies.

This is not to say that the characters come to renounce religious faith. None of the people in Go Tell it on the Mountain, least of all John, rejects the Holiness Church’s practices or beliefs. But some, like Florence, have made a break from constant religious fanaticism and banter. At book’s end, the characters assemble for an all-night prayer service, which spins into a spiritual catharsis, with John at its center. At dawn the next morning, they walk out of the church with a deep feeling of emotional resolution. But the reader closes the book suspecting that, despite this night of intoxicating prayer, this faith will never unshackle any of their lives, especially those who are most ardently engaged with it.

The same insight that crafted this wise novel also compelled its author to choose the path that led away from Christianity.

As I worked through the novel, I wondered if a devout Christian might see Go Tell it on the Mountain’s fictional congregation as admirably spirit-filled, morally strenuous, and a shield against White race hatred. In other words, Baldwin’s critique is subtle. As a minister, I was awed at his grasp of Christian faith. I couldn’t escape the thought that it takes a savvy theological mind to see how Bible passages can be twisted; Christian ideas, deformed; and God’s grace, bypassed. Baldwin has hidden hundreds of micro-heresies throughout the book. These work together to produce the monstrously deformed Christianity that reinforces the tragedy of John Grimes’ family.

I hunted unsuccessfully for some life-affirming power in the garish religion practiced by the three generations of characters. Certainly, Baldwin, who knew the Scriptures and prayed, would have experienced Christian faith’s deliverance in his own life. But he argues insightfully that these resources were simply not there either for his characters or for him.

I was reluctant to settle on the stark conclusion that Go Tell it on the Mountain is an altogether negative critique of religion. I hunted up Baldwin’s 1962, “Letter from a Region in My Mind” in order to reacquaint myself with what he said plainly about Christianity years after he wrote this first book. I found in “Letter” the logical outcome of what I was seeing in the novel. Baldwin walks out of church in his late teens, three or so years after he has his own transformative experience. James doubtless uses his own religious experiences as a pattern for those that John undergoes. In “Letter from a Region in My Mind,” Baldwin knows about Christianity’s promise and grandeur. But he’s skeptical that he can reach it. Indeed, he feels Islam is more congenial to the Black struggle, but rejects becoming a Muslim after a dinner with Elijah Muhammad. About three years after James is “saved” in his teens, he spends the balance of his life as a firm non-adherent. The conclusion is inescapable. Go Tell it on the Mountain sets forth a shattering appraisal of religion.

The Story

The novel is autobiographical fiction. Baldwin projects himself into the main character, fourteen year old, John Grimes. John is at a terrifying crossroads. Down one path is salvation, Holiness-style, with its promise of personal righteousness, spiritual joy, and importantly, resolution of the crossroads problem. Down the other path are the “streets,” which, according to John’s church and family teaching, lead to certain damnation. Early in the story this crossroads decision wells up in John and Baldwin describes its power:

Suddenly, sitting at the window, and with a violence unprecedented, there arose in John a flood of fury and tears, and he bowed his head, fists clenched against the windowpane, crying, with teeth on edge: “What shall I do? What shall I do?”[1]

John is deeply vexed as he tries to choose his path because he knows that if he continues in the church and his religionized family, he will lose himself in his morally decrepit father’s pathologies. By walking out of family and church, on the other hand, John becomes free to explore the beckoning traces of beauty and love he senses on the outside. This is not to say that all is wonderful on the streets. The streets or the world outside the church-family enclosure, is the place of death and damnation, according to the Church’s judgment . This conclusion is not an entirely wrong judgment for poor Harlem residents during the 1930’s.

Additionally, John feels rushed to choose his path. His family and congregation feel that John is of age to undergo an ecstatic conversion experience, which in John’s mind will seal him in religion’s embrace.

What the reader discovers, as the narrative jumps back and forth between John’s forebears and the 1935 Saturday night Tarry Service is that each of the characters has navigated his or her own version of John’s crossroads. The book’s climax occurs when the Terry Service’s emotional energy sweeps John into his long-anticipated ecstatic vision, deemed by the Holiness tradition as certification of the adherent’s connection with God. By this point, the reader is well-acquainted with the principle characters and is probably skeptical of the Grimes family’s religion, which has, throughout the book, brought little but suffering. On its surface, John’s ecstatic experience suggests that he has “gotten religion” and taken the religion branch of his crossroads. What John actually sees as he rolls on the dusty church floor, will, with time, guide his steps down the other path.

The Book’s Structure

The narrative follows a loose chiastic structure, which can be seen here.

Through a chiasmus, the author guides the reader to the story’s center. Go Tell it on the Mountain can easily confuse even the most attentive reader with its flashbacks, the scattering of character information in non-chronological fashion, and complex family inter-relationships. When the reader sees how the novel revolves around Gabriel’s path, which culminates with Esther and Royal’s deaths, it is easier to understand that Baldwin is criticizing Gabriel’s style of faith. What emerges from the confusion of characters and relationships is Gabriel’s despicable religiosity and a sense that John ought to get out of that situation.

A genogram (click to download or for a closer view) plot of the book’s characters and their relationships with one another, underscores Gabriel’s centrality.

Gabriel

Gabriel is a morally vile individual, filled with cowardice and poor impulse control. He is also his mother’s youngest child, the last of several children—some born in slavery. Upon his birth, Gabriel’s mother focuses all of her energies and aspirations on her baby boy, to the exclusion of his older sister, Florence. Gabriel’s mother’s belief is that her son is destined to follow a holy path through his life.

While Gabriel eventually experiences a call to preach, he spends some of his early years addicted to a lifestyle centered on alcohol and prostitutes. He finally undergoes a kind of spiritual call, after a night of carousing, as he stumbles back to his mother’s house in wee hours of the morning.

“Then,” he testified, “I heard my mother singing. She was a-singing for me. She was a-singing low and sweet, right there beside me, like she knew if she just called Him, the Lord would come.” When he heard this singing, which filled all the silent air, which swelled until it filled all the waiting earth, the heart within him broke, and yet began to rise, lifted of its burden; and his throat unlocked; and his tears came down as though the listening skies had opened. “Then I praised God, Who had brought me out of Egypt and set my feet on the solid rock.”[2]

Baldwin’s description here of Gabriel’s conversion or call is an example of a device he uses repeatedly to indicate the phoniness of Gabriel’s religion. The reader might expect that Gabriel’s nighttime spiritual crisis and calling to the religious life would be more God-centered. One would expect a strong note of forgiveness for his moral lapses. What Gabriel actually experiences is a vision of his mother’s yearning for his life. Gabriel would retell this story to congregations as a way of certifying his authorization to preach. But there is no such authorization, even in Gabriel’s recounting of the event.

Early in Gabriel’s preaching life, he is flattered to be included in a lengthy revival program, which is led by 24 notable ministers. Gabriel’s sermon, drawn from Isaiah 6, is a surprise success and it yields one convert who comes forward at Gabriel’s invitation. The scriptural text recounts the prophet Isaiah’s feelings of being overwhelmed and humbled upon seeing God in the Jerusalem Temple. “Woe is me,” cries Isaiah feeling unworthy. God’s graceful response is to touch Isaiah’s mouth with a burning coal, thus purifying his speech. The themes of unworthiness and authorization to speak intersect with Gabriel’s personal situation, a fact that he ignores in the sermon, which focuses on Isaiah’s cry: “Woe is me.” (Isaiah 6.5). The message snatches judgment from the jaws of grace, which is characteristic of Gabriel’s ministry and the holiness tradition to which he belongs.

The accumulated effect on the reader is the impression that Gabriel and the holiness tradition to which he belongs will forever be in the wilderness of striving, never quite arriving in the Canaan of peace.

Gabriel repeatedly reports that God sends him messages and organizes his life events in a manner that ingeniously justifies whatever evil he has perpetrated. At the culmination of Gabriel’s section, when he learns that his illegitimate son, Royal, has died, as has his mother, Gabriel weeps in the presence of his wife, Deborah, whom he has deeply betrayed. Gabriel might have acknowledged his responsibility and acted to support Royal and his mother, Esther. But Gabriel has preserved his public reputation as a preacher by keeping secret the fact that he has this son. Stunningly, Gabriel credits God with holding him back from acknowledging and supporting Esther and Royal in order to keep him from being “dragged right on down to Hell with her,” because “Esther’s mind weren’t on the Lord.”[3]

In Gabriel’s hands, religion, becomes a tool of self-justification and manipulation of others. instead of a transcending force for deliverance and joy. Gabriel sanitizes his cowardice and lack of self-control a flood of religious blather. His stance in relationships is always at the pulpit, calling family members to a new slavery of humility and striving. Small wonder John is apprehensive about undergoing the conversion experience that would cement him permanently in his religionized family.

Florence and Elizabeth

The novel’s chiasmus reveals a similarity between Florence, Gabriel’s sister and Elizabeth, his second wife and John’s mother. Florence’s story comes immediately before Gabriel’s; Elizabeth’s comes immediately after. As a young woman, Florence negotiates the choice between the “streets” and her religionized family by walking out on her sickly mother and brother, Gabriel, in order to travel to New York City. Florence’s rejection of her religionized family is her decisive step in becoming the novel’s most admirable character. For example, Florence is a powerful truth-teller throughout the story. She screams vividly accurate rebukes of Gabriel’s character flaws during the family melee that follows Roy’s stabbing injury, early in the book. At book’s end, Florence verbally skewers Gabriel with deliciously delivered revelations, which thoroughly unmask Gabriel’s sordid background.

Florence shows kindness, significantly to Elizabeth in her bereavement and loneliness in New York City. Earlier, Florence and Deborah were fast friends as young women in the South. Florence’s relationships with these two women who would become Gabriel’s wives were much more grace-filled than their religiously tinged marriages.

By the time readers reach Elizabeth’s story they are wary of religion’s oppressive potential, despite the energy of worship and the ardor of preaching. Elizabeth’s young adulthood is squeezed in the iron grip of her religious aunt. But Elizabeth’s lover, Richard, a character completely separated from religion, wins her attention and love with a wholesome flirtation. As their romance blooms, they escape Elizabeth’s aunt and the South and move to New York City. Richard not only loves Elizabeth but life and the world. The couple visit museums and galleries, and in this spacious, non-religious world of ideas and love, John is conceived.

Sadly, in Go Tell it on the Mountain’s construct of reality, the non-religious streets both sparkle with grace, and are haunted by race and death. Just as the reader is cheering for Elizabeth and her broad-minded lover, New York City police mistakenly arrest him. All of events of racialized oppression described in the story, leave their victims deeply damaged, and Richard is no exception. Even though he is exonerated, he returns to his apartment, cuts his wrists, and leaves pregnant Elizabeth distraught and alone.

Fortunately, Florence, a co-worker with Elizabeth, helpfully embraces Elizabeth and her infant. Unfortunately, Florence’s brother, Gabriel, newly freed from marriage with Deborah’s death, moves to New York City. Gabriel promptly focuses his religion-saturated romantic attentions on Elizabeth and her little boy. In her state of vulnerability and against Florence’s wise counsel, Elizabeth succumbs to Gabriel’s wooing. The two are married, Gabriel resumes preaching, and three additional children are born to them. As years pass, John moves to the edges of Gabriel’s attentions, which are focused on his biological son, Roy. John, emotionally isolated, reaches his fourteenth birthday, and faces his difficult crossroad’s decision, which will be resolved on the dusty floor of his family’s church.

The Threshing Floor: John’s Ecstatic Vision

Go Tell it on the Mountain reaches its climax in John’s hours-long euphoric vision, which he experiences during the tarry service. Holiness adherents expected their young adult participants to undergo such ecstatic dream states, which served to signify God’s authorization of the believer’s entry into the fellowship. What is unexpected, is what Baldwin has John actually see and feel during his dream state. Instead of divine endorsement of Gabriel’s brand of faith, John sees his step-father as a violent devil-figure at the bottom of a deep pit. Instead of bringing joyful release from oppression, the religion which John perceives in his dream shows church people wandering around in unending misery. Once again, Baldwin uses the outward forms of religiosity, in this case a visionary experience, to carry a subversive message. The message and the vision combine to give John—and others around him–release from anxiety over his crossroad’s predicament and permission to launch eventually down the path that Florence had taken years before, the path of Richard and Esther, the path out of the church doors and into the “streets.”

Church Take Heed

In the Christian Church’s early centuries, its leaders realized that some groups of believers had twisted beyond recognition the religion that Jesus came to give. Theologians call this phenomenon a heresy. Nineteenth-century theologian Friedrich Schleiermacher defined heresy as “that which preserved the appearance of Christianity, and yet contradicted its essence” `

Go Tell it on the Mountain’s fictional church and the idea system that animates it probably would not qualify as a classic heresy, a term reserved for doctrines, which contradict church-wide consensus about what constitutes the faith. That said, the congregation in Go Tell it on the Mountain, especially where Gabriel has control, enjoys all the fire and excitement of a Spirit-filled piety, while all the while is held in the thrall of a truncated version of the Gospel. The faith that surrounds John Grimes is wilderness that never reaches a promised land; law without grace; guilt without deliverance; revelation without truth; slavery without emancipation. This brand of faith becomes a power tool of oppression when it merges with family relationships, where parents beat the sin out of their children and women become marriageable only after they come forward in an evangelistic service.

In exquisite detail and subtlety, Baldwin portrays across the span of three generations, an empty religiosity that nevertheless retains the trappings of vitality. Baldwin is enough of a theologian to know what a biblical text means and how a sermon, even when delivered with roaring homiletical bombast, can steer its hearers away from that meaning. He gives us a couple of these in his novel. Baldwin knows what God’s calling is, what a conversion is, what a vision is. And he knows equally how to depict them in such a way that they retain the form of spiritual power while lacking the content. Baldwin knows what religion looks like that makes no difference,

It’s important to be clear that Baldwin isn’t critiquing the Black Holiness tradition. Go Tell it on the Mountain is fiction after all. But his insights are too penetrating to be completely fiction. He has seen what he portrays. He knows a congregation’s naiveté, which a preacher can exploit. Baldwin himself stood in pulpits and manipulated congregations. He also knows that he can sometimes find truth and compassion in the death-dealing “streets,” supposedly destined, as the church warns, for everlasting fire. The same insight that crafted this wise novel also compelled its author to choose the path that led away from Christianity. Baldwin was later to say that he “left the church to preach the gospel.”

Church leaders have much to learn here. There’s no substitute for the truth in faith no matter how exciting the worship or numerous the attendees. Leaders, like Gabriel, who present a false image in order to be elevated in their leadership will engender cynicism and abandonment by those who know the truth. Loyalty to the full message of Christian faith, rather than the parts that are easy in the moment. There’s nothing like the Bible to drag preachers, teachers, and congregants into areas of faith that are difficult or not popular. Finally, keeping an eye on the big picture will keep congregations centered on the heart of faith. During John’s rapturous vision at the novel’s end, in phrases reminiscent of the Book of Revelation, John (Grimes) sees:

…The river, and the multitude was there. And now they had undergone a change: their robes were ragged, and stained with the road they had traveled, and stained with unholy blood; the robes of some barely covered their nakedness; and some indeed were naked. And some stumbled on the smooth stones at the river’s edge, for they were blind; and some crawled with a terrible wailing, for they were lame; some did not cease to pluck at their flesh, which was rotten with running sores. All struggled to get to the river, in a dreadful hardness of heart: the strong struck down the weak, the ragged spat on the naked, the naked cursed the blind, the blind crawled over the lame. And someone cried: “Sinner, do you love my Lord?”[4]

In prose that echoes with the cadences of John of Patmos, Baldwin paints a picture that is akin to Dante’s scenes of eternal hopelessness. The big picture here is the sobering insight that deliverance never comes. This novel challenges Christians to step back from church routine and courageously ask, “Is goodness, truth, and beauty here? And if not why not?”

[1] Baldwin, James. Go Tell It on the Mountain (Vintage International) (p. 24). Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

[3] Ibid. pp. 147-148.

[4] Ibid. pp. 206-207.