Creation Versus Chaos–Review

Back in the mid-1970s when I was one of Bernhard Anderson’s seminary students, I had no idea that my teacher was a pioneer scholar at the forefront of the Christian world’s “turn to creation.” Anderson authored this book about ten years before I took his introductory class on the Old Testament.

Not only did I not know of Anderson’s focus on creation in the Old Testament, I probably wouldn’t have understood the problem he was wrestling with, which, stated simply is that Christianity had let the element of creation fade to insignificance. Scholars focused on other biblical themes and ministers preached and taught about other things.

It isn’t as if no one realized that “In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth…” It’s that Old Testament scholars weren’t talking about it or writing books about it. Creation had for centuries occupied a place as the backdrop for the more exciting drama of God’s saving acts in history, like the call of Abraham or the advent of Jesus Christ.

Then came the 1960s and the environmental movement and theologians jolted awake. “We’ve got nothing to say to a problem that threatens all of life on the planet.”

Today, the environmental issue has bloated into global warming, a crisis of apocalyptic proportions. And Bernhard Anderson’s original awakening to the menace of environmental collapse is as important today as it was a half century ago.

Anderson wrote Creation Versus Chaos in response to a problem that is the same in character as the one we face today. Unfortunately, global warming is many levels more threatening to all life forms than say, water pollution. The beauty of this book is that it comes early in a string of studies that would span the next 30 years, culminating with Terence Fretheim’s brilliant, God and World in the Old Testament.

My close reading of Creation Versus Chaos has significantly advanced my insight into the role that creation plays in biblical faith. But even more importantly Anderson likens the disorder of social uproar, war, pestilence, and famine to the primaeval chaos that was the Creator’s most original adversary.

Stated in glorious simplicity: the chaos then is the same chaos we have today.

This linkage has nourished my personal conviction that the biblical theology of creation is a deep resource for responding to the disorder, if I can use that word, of climate change. Anderson could have just as easily cautioned readers from too easy an identification of today’s headlines and social media posts with the mythic waters out of which the cosmos was born. Instead, he shows how the Creator—Chaos tension persists after the Seventh Day when God took a day off to enjoy all that he had done, which to that point was “very good.”

Put differently, Creation isn’t about the beginning of things. It’s about the nature and destiny of the world today. One important and neglected aspect of creation is that God still creates. We see this creative activity through the Old Testament, not only with natural elements like wild waters, but also human chaos like the injustice in Egypt that enslaved the Hebrews for centuries. The process of wresting Israel from Pharaoh’s hand was, if you read carefully, creation-like. The Pharaoh, in declaring himself divine and enslaving the Israelites, put his empire on a downward slide, which the Bible describes as creation in reverse. Nature goes out of whack in the ten plagues. Pestilence rages with devastating results. There’s even the dividing of waters to bring something new, a new nation, into existence.

To read the Bible with creation in view is to find it, not as an incidental curiosity, but as a commanding metaphor that describes the character of God’s work.

It’s this continuing creation through the Scriptures that encourages me to see our present climate crisis as an extension of the primaeval chaos out of which God drew light and life. Anderson has reinforced my hunch that I’m on the correct path in looking to biblical creation for insights into the climate mess we’re in today.

Creation and Chaos has opened other intellectual windows for me. Creation Versus Chaos does not ignore the sausage making aspects of the Old Testament. Human beings told the stories and wrote them down in what became the Old Testament. The process took a thousand years and originated from a variety of faith perspectives.

For example, Anderson has shown how to deal with the jarring fact that Israel borrowed mythological elements from its Mesopotamian neighbors and incorporated them into its creation stories. Early Mesopotamian civilizations that predated the Biblical Israel, told of their own watery chaos that needed a heroic god to defeat them for the world to come into being.

Old myths tell the story of a flood and a boat that rescues people and animals. When Christianity discovered these old stories in the 19th century, they created more than small controversy. But as Anderson points out, Israel’s genius was not in coming up with entirely new content, but entirely new meaning.

Sometimes the Bible loses gravitas when we learn that parts of it were not written at a time or by the people, we long thought were its sources. Anderson appears undaunted by this seeming unoriginality. He finds important meaning in the twists and turns that the text has taken on its long journey to the present. When we see how the Bible shares elements with Mesopotamian creation myths, we not only get a sense of interdependence between Israel and its neighbors, but also differences.

It helps me to imagine the careers of movie stars as they move from film to film. Take as an example the versatile and enduring actor, Meryl Streep. Among her roles she won an Oscar for her work in the drama, Sophie’s Choice. In that film she played a holocaust survivor in a tragic situation. Years later she played Julia Childs the television chef in a light movie, “Julia Julia.” No one would say, “I cried all the way through “Sophies Choice”, and I don’t want to leave the theater depressed if I see ‘Julia, Julia.’” The reason no one says that is because movie-goers understood intuitively that the thrust of any movie is the story it tells rather than the actors who play roles.

When the Bible uses mythology from other ancient societies it isn’t merely copying. The Bible takes familiar elements and reshapes them so to tell a different and innovative new story

What Does All of This Have to Do with Climate?

Despite Christianity’s silence on climate change, the faith does have theological resources that may prompt the kind of change of consciousness that will be necessary to turn the world away from disaster. In the 1960’s we were getting our first glimpse at humanity’s ability to damage the world. Back then we were thinking primarily about pollution and the destruction of natural areas.

And the church, like the deer frozen in the headlights, found itself paralyzed, while an informed public, students, and politicians went to work addressing the problem. The first Earth Day and the launch of the Environmental Protection Agency popped up within months of each other.

But pulpits were silent.

There were church leaders back then, academic theologians mostly, who were clear-eyed about the church’s long-time neglect of the created world. These scholars turned their attention freshly to the familiar biblical texts that told the creation story, and they unearthed a trove of new insights. Through the 1970s and well into the new millennium, these scholars’ books and papers piled up—unread. Unread at least by preachers and congregations. This significant theological work with all its transformational potential continues to be available to the church as it faces with the entire living world a monumental challenge.

Chapter 1: Creation and History

One reason that this book feels timely and sheds light on our current crisis of climate change is because Anderson links the social disorder of the mid-1960s with the chaos in Genesis 1. On Creation Versus Chaos’s first pages, he cites Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the popular song, “Eve of Destruction” as contemporary manifestations of the primaeval chaos. Put differently, the wild and dark waters of the Bible’s first verses have persisted not only through Israel’s story but throughout history. This persistence of chaos is an important idea which ties the creation stories and creation theology to the crises of the present, preeminently the crisis of climate change.

The idea of chaos is not unique to the Bible but was commonplace in ancient Mesopotamian mythology. Archeologists unearthed and translated the cuneiform tablets that recorded Mesopotamian myths in the late 19th century. The Christian world began to learn, for example, that the god, Marduk slayed the chaos dragon, Tiamat in the ancient story behind Babylon’s beginnings. It’s reasonable to speculate that migrants from Mesopotamia carried such stories with them as they made their way into what became the Israel of the Old Testament.

We’re only just learning this. Christians have had to reckon with the fact that biblical editors borrowed images like chaos for a couple of hundred years. That the ancient biblical editors incorporated unoriginal material into the scriptures seems to diminish the Bible’s authority.

Anderson deals with this. While the Bible uses Mesopotamian mythology, it does so to support a uniquely biblical view of the world. Myths are dramas that play out in a period before the start of history. Marduk slays Tiamat and sets up Babylon on her dead body. The king and priests reenact the myth in an annual religious ritual, an exercise that has power to inject the original creative energy back into the society.

The biblical use of a chaos element sees the creative process as unfinished and continuing. The biblical Creator brings order to chaos in a seven-day process and doesn’t quit creating. Creation in the Bible merges with history. Later in the deliverance from Egypt recorded in the Exodus story, the drama of creation continues with the freeing the slaves and guiding them through the Wilderness.

While some of the elements in Genesis’ first 11 chapters are familiar mythological elements, the biblical view of the world is deeply different than that of the mythic outlook. The gods of the myths function in mythic time. Their creative energies are retrieved liturgically through sympathetic magic enacted by priests and king. The biblical creator does not live in a time before history. God is actively working on the creation project, which ebbs and flows through history and will culminate gloriously in the end of all things.

This modification of the mythic structure of reality from cyclical and unchanging to historical and developing is indeed unique to biblical religion. Anderson notes that Karl Barth advocated for replacing “myth” with “saga” when describing the biblical view of origins and history.

Chapter 2: Creation and Covenant

Israel held a new idea for its god’s presence and guidance of its national life. The typical pattern of ancient societies was to trace their existence as a people to a glorious creation myth. Israel saw its creation to be rooted in God’s historic intervention that released God’s people from slavery in Egypt. Put simplistically, in its early years, namely during the Tribal Confederacy period, Israel was “up and running” as a nation with a story of its own founding. Israel didn’t have a story of how the rest of the world as a whole got started or what its nature and destiny was. Israel lagged in incorporating a creation myth into its faith.

Anderson uses this second chapter to present one scheme that would account for the first three chapters of Genesis, the “creation stories,” and the creation faith that threads though the rest of the Bible.

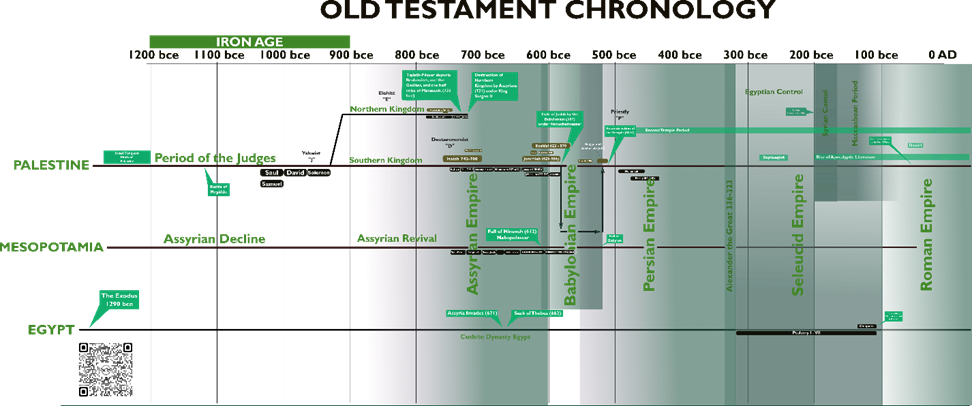

Anderson suggests that they developed in Jerusalem in the 900s b.c. as David’s monarchy and the Temple traditions were gaining vitality. Anderson pulls together several strands of evidence to show how Jerusalem had become a theologically generative place under David and Solomon’s leadership and produced the kind of thinking implicit in the creation narratives.

Anderson sees the rise of David and Jerusalem as the cultic center if Israel’s life as momentous developments. Put differently, Israel was becoming confident because it finally had a stable Monarchy plus a vital religious life centered on the Temple. Out of this convergence grew what I’ll call “creation thinking” that fostered the development of distinctly Hebraic creation stories that interwove with the salvation history.

What he does describe is the mashup of traditions and influences that converged in 10th century b.c.e. Jerusalem that fostered “creation thinking”—my term. Convincingly, he shows that such thinking, including the creation stories themselves in Genesis 1-3, seem to appear in the time and place we’re describing.

Genesis’ creation narratives, while they tell of the world’s start and character, are a logical second step beyond redemption. And the fact that there is no record of a scribe picking up a stylus 3000 years ago and writing down, “In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth…” means that for anyone to speculate persuasively about the origination of creation thinking, as Anderson does in this chapter, is an impressive intellectual achievement.

Here’s how he does it. He lays out two fundamental streams of tradition that thread through the Old Testament. These predate the Bible and are rooted in Mesopotamia on one hand, and Egypt on the other.

One characteristic of Mesopotamian societies was the pervasive upheaval they endured. Unpredictable weather and political uncertainty subjected the Assyrians and Babylonians to precarious living conditions. Egypt, in contrast, relied on the Nile’s annual flooding which replenished the soil. They royal house of pharaohs was equally predictable providing the Egyptians with a stable succession of leaders and relief from political uproar. The myth systems of Mesopotamia and Egypt followed their respective experiences: the former had wild myths; the latter, more serene.

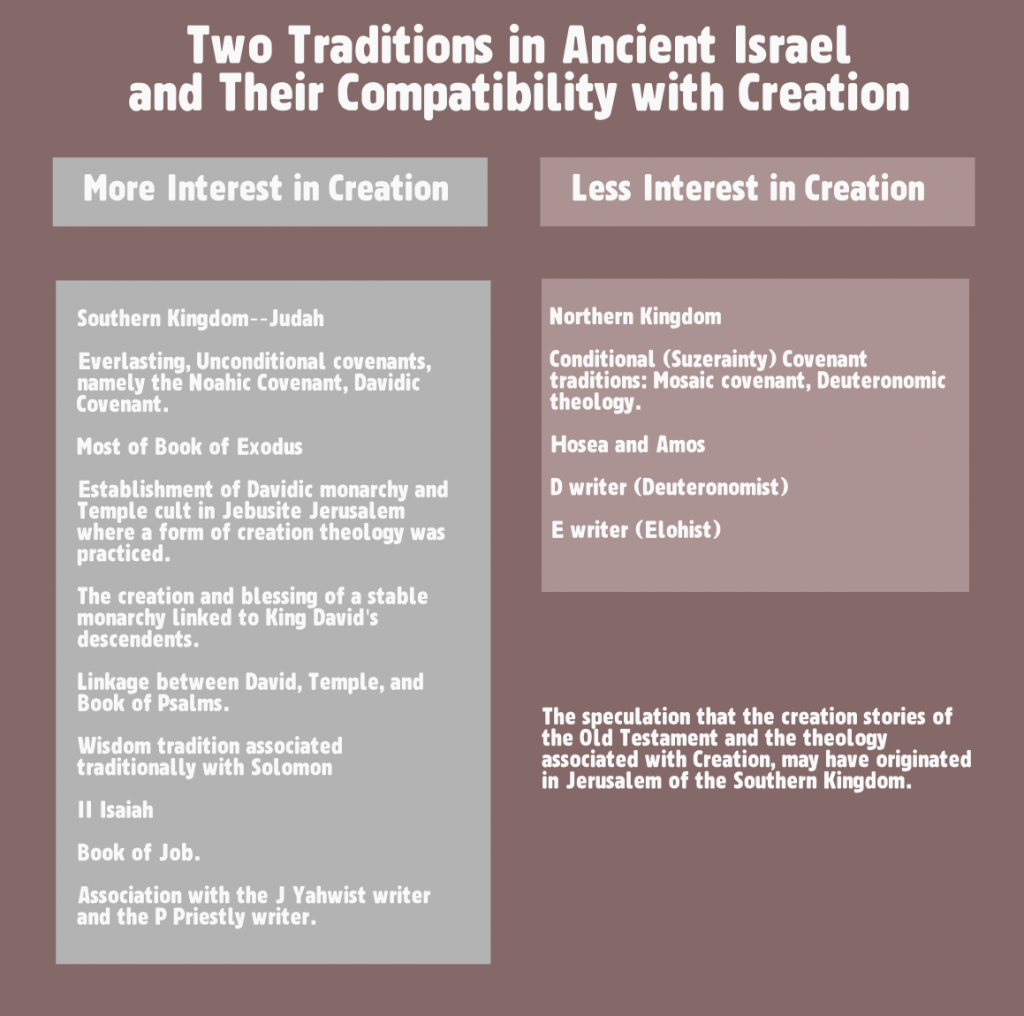

The two theological streams within Israel’s experience, which Anderson teases apart, correspond to the wild and serene of the neighboring empires.

The divided kingdom, consisting of Israel in the north and Judah in the south is no superficial fracture. It began at the end of David’s reign and ended with the destruction of the Northern Kingdom at the hands of the Assyrians.

This fracture ran deeper than a territorial distinction. Each kingdom had its own king and different religious emphases.

What this chapter proposes is that Judah’s theological emphases of were much more compatible with the kind of thinking that underlies the creation stories. Some examples will illustrate:

Chapter 2’s title is “Creation and Covenant.” A covenant is a contract or agreement between two parties. The Old Testament uses the idea of covenant as a metaphor for God’s relationship between Godself and the world or God’s people. Two kinds of covenants appear in the Old Testament, the suzerainty and unconditional covenant. A suzerainty covenant is an arrangement that powerful empires impose on weaker neighboring kingdoms. Like a protection racket, the powerful King pressures the weaker to keep burdensome tribute payments flowing while refraining from rebellion or alliance with enemy kingdoms. You do this and I’ll do that. The Mosaic Covenant is a form of the suzerainty arrangement. God says to the people, “you obey the Law and I’ll lead you into your own land and let you flourish there.”

The everlasting covenant is simply a promise. God says to Noah, “I’ll never destroy the world again with a flood;” or to David, “You and your descendants will always be the kings of my people.” Anderson sees the creation as infused with promise or an unconditional covenant, which was a core animating idea in David’s Jerusalem.

Anderson further points out that Jerusalem, even before David conquered it and set up his capital there, was under the control of the Jebusites, a Canaanite people who had a strong theology of creation. It is likely that, as Anderson puts it, when David captured Jerusalem, he also captured a creation theology. If the Israelites allowed or even encouraged the Jebusite cult to continue after David established his base there, then there was more syncretism in play than we ordinarily imagine.

There’s more. The Documentary Hypothesis attributes the Genesis creation stories to the J and P sources which scholars associate with the Southern Kingdom. The E and D sources are more linked with the northern tribes.

It’s worth saying that the Documentary Hypothesis does not enjoy the scholarly consensus that it did when Anderson wrote in 1965. Notably, Old Testament scholars now think that the J source was committed to writing in the 6th century BCE. Anderson is aware of shifting support for the various aspects of the Documentary Hypothesis and he asserts that long before the various Old Testament sources were committed to writing, they had lengthy oral traditions. If he is correct here, then locating creation narratives in the early monarchy and thus within the worlds of J and P is plausible.

Anderson is confident in his conclusion that early monarchy Jerusalem was where creation faith fused with Israel’s emphasis on history. At first Israel saw “creation” as God’s bringing it into being.

Finally, in the Psalms we see a convergence of God’s establishment of David’s kingship, his appointment of Zion as the site of the Temple, and the creation of the heavens and the earth. Again, we are guessing through association. The psalms were part of the Temple’s sung liturgy. In the psalms are praises for the establishment of the Davidic monarchy the Temple and Creation.

Chapter 3: “Creation and Worship”

Anderson begins his third chapter, “Creation and Worship” by reflecting on how creation faith functioned in Israel’s worship, especially in the Psalms. He begins by making an important point. Creation faith isn’t about having knowledge about how everything came into existence. It’s about receiving an orientation to the value and purpose of the world we find ourselves in. It’s also about our personal vocation as created beings within that world.

Aware of the world’s value, God’s ongoing work in the world, and our role in creation, people find themselves inclined to worship the God of creation. We can see this in Israel’s worship, especially in the Psalms which preserve a record of what the people said and sung when they gathered for various rites and celebrations.

For example, the 8th Psalm gives voice to the human dilemma of feeling insignificant in the face of the vastness and beauty of God’s creative work all around. Yet, the Psalmist also knows that in the creation stories, the Creator gives humans significance and work to do. “Yet thou hast made him little less than God, and dost crown him with glory and honor.” (Psalm 8.5)

Psalm 104 is a stunning example of the merger of creation faith and worship. The reader of this psalm will notice that the progression of themes in the psalm follows the work of each of the days of creation in Genesis 1. Early in the psalm we read of light, heavens, waters, and wind. We progress to land and animals and come to culmination with the breath of life.

Anderson then turns to a fascinating and little understood insight about the Old Testament. Creation theology merges with Israel’s historical faith, which sees God working out its salvation in the events of its history.

A passage in Jonah is representative. The prophet Jonah is in personal distress because sailors have thrown him into the sea and a great fish has swallowed him. Jonah says, “Out of the belly of Sheol I cried, and thou didst hear my voice.” But then Jonah employs creational language: “For thou didst cast me into the deep, into the heart of the seas, and the flood was round about me; all thy waves and thy billows passed over me.” This is one place among many that we see a merger of familiar creational language and the language of personal rescue.

Chapter 4 “Creation and Consummation”

If we were to put Anderson’s argument on a timeline, it would begin in the mythological traditions of civilizations which surrounded ancient Israel, notably Babylon and Canaan. Israel, in turn, brings into its creation stories elements of its neighbors’ creation myths. In using elements like chaos and flood Israel recasts the essential meaning of these stories. This process is much like collecting used lumber from a dilapidated barn, sawing it into fresh boards, and putting them together into a new home.

As Israel appropriates familiar stories it makes essential changes to their messages. Anderson focuses on one transformation that gives Israel’s faith much of its unique character. Traditional societies like those in Mesopotamia and Egypt, saw the events of their society’s beginning as taking place in the distant past in a special time before time. We say “once upon a time” when reading fairy tales, which is a way of communicating that the story didn’t take place in the course of ordinary history.

Creation myths take place in a time before time and release the unique energy and characteristics of the society coming into being. This origin myth is a one-time start up. The energies and freshness of the start can however be retrieved through ritual enactment. Periodically, say annually, the priestly leaders restore in ritually in some kind of new year’s celebration which re-enacts the enthronement of the king who serves as a stand-in for original creator. This annual reenactment gives the history of a society a cyclical character. The reenactment prompts a cosmic reset which reestablishes the society’s original integrity. And it does no more than this. History isn’t going anywhere in the sense that the society is getting better and better. It’s simply recharging itself in a communal worship event, which reclaims the energy of its founding.

Israel, in contrast, historicized its conception of creation. Instead of seeing itself in a cyclic framework, which routinely brings the world back to its original state, Israel saw the creation of all things as unfinished and ongoing. Israel may have had an annual creation festival as did its neighbors. Israel’s annual enthronement ritual celebrated the Creator’s ongoing work of creation. In other words, the battle against disorder is unfinished. Creation is well advanced and on a good track by the end of the first week as narrated in Genesis 1. But chaos persists and even surges forward. This dilemma requires God to work to push it back in a manner reminiscent of the original creation.

Creation Versus Chaos’ fourth chapter begins by observing that continuing creation implies the prospect of a completed or new creation, a prospect that appears numerous times in the Old Testament, especially in II Isaiah. All three presentations of creation manifest the quality of creation first seen in Genesis 1 and 2. The idea of creation is not entirely a matter of recapitulation. Creation is the Creator’s bringing something entirely new into being.

Mid-chapter, Anderson makes observations about sacred time and sacred space in Israel’s worship life. As with creation mythology, Israel borrowed elements from cultures which surrounded it. Sacred spaces in the ancient mind are places of intensive divine activity, usually in the past. Traditional religion saw some places, often mountaintops, as sites where God might manifest godself again. A sacred site would be a good place to build a temple or altar. The temple would be constructed on the pattern of a heavenly or divine temple. The Jerusalem Temple, for example, corresponded to a heavenly temple. Israel freely adopted the ancient conception of sacred space.

Israel, however, was more focused on sacred time and it made modifications to their neighboring peoples’ idea of time’s passage. The ancients saw the ultimate destiny of their history to be identical with the ultimate beginning. Events such as wars or changes in leadership or prosperity arose, the ancients interpreted these in a framework of “times.” For example, there may be a season of famine which would be a difficult “time.” The ancients saw this succession of times as temporary. In the end, the gods would restore all things, much like an original factory reset of a stereo or television unit.

Israel, in contrast, saw history as pressing to a new creation, like the original creation, but with surprising newness. The ongoing creation, which involves God, humans, and the creation itself, presses to something new. This outlook confers purposefulness on each day, where the mythological view was a true embodiment of the old saying, “the more things change, the more they stay the same.”

Anderson suggests that Israel invented the practice of shifting the meaning of holidays from their agricultural focus to remembrances of decisive historical developments, such as the Exodus or the giving of the Law at Sinai.

He then moves at this point to a discussion of II Isaiah the Old Testament’s leading prophet of the merger of creational with historical thinking. Writing after the fall of Jerusalem, likely in exile in Babylon, Isaiah says repeatedly that his people’s plight and Babylon’s power was dwarfed by the Creator God who brought into being the heavens and earth. Several characteristic themes benefit from Second Isaiah’s use of creational imagery. He, for example, sees God as creating Israel itself anew. He predicts the return from exile as a new exodus, which itself was a creational act.

Creation in the Old Testament then begins being about the origin of what we would call the natural world. It moves to include the creation and continuing creation of the social world.

In summary, Isaiah sees creation as eschatological. His predictions and optimism cast the future in the language of God’s making of the world in the first place. Put differently, by historicizing creation, by seeing God at work continuing to create, a picture of the ultimate future begins to emerge.

The images of creation and especially chaos proved useful for several other Old Testament prophets. They used creation as a metaphor to frame their interpretation of the crises that confronted them. As the tradition of the classic prophets gives way to apocalyptic literature around 200 BCE, the use of the old mythological images of the non-Israelite kingdoms abounds.

The element of YHWH’s ongoing creation amid history gives way to a rival image of history as conflict with embodied evil. The character and development of evil in the Old Testament will be the topic of Creation Versus Chaos’ fifth chapter. The profusion of monsters, dragons, and lurid characters in the Book of Revelation illustrates this shift from organizing chaos to battling evil. In Revelation the defeat of evil, now represented by Satan, is a divine project. What seems to have dropped from view is the back and forth battle of continuing creation, God needing to retreat for a time and then able to advance again. Apocalyptic sees history as the stretch between creation and new creation. The human actors function by preparing themselves for God’s eventual triumph. It is in apocalyptic thinking that the messiah plays a crucial role. The messiah is a heroic warrior figure who defeats the overwhelming forces of evil and brings into being the New Creation.

Chapter 5: Creation and Conflict

By “conflict” Anderson means the powers that array themselves against God’s work, namely evil. This chapter is particularly fresh and useful and I summarize and expand on it here and here. To summarize: in the same way that creation thinking merges with Israel’s view that God showed Godself as Israel’s savior through mighty acts in history like the exodus, so does the conflict between creation and chaos give way to a conflict between God and Satan by the time of the rise of Christianity.

Conclusion

Anderson wraps up Creation Versus Chaos by reflections on practical applications of his insights. In the Epilogue he observes that the chaos motif continues to be a useful metaphor to describe evil or that which God opposes. I the Postscript Anderson ventures some speculations in the ways that the Genesis Creation stories put the Bible in conversation with cosmological questions often entertained by science. Creation indeed has something to say about “the mystery of origination, the mystery of order, and the mystery of the emergence of life. Science has not given definitive answers to these mysteries and stands before them much as the bible does, namely humbled by their mystery.

This final insight comes close in my thoughts to the overall promise of recovering biblical creation. Creation broadens faith’s horizons. Instead of seeing Christian faith as preoccupied with the redemption of the individual adherent, the creation element opens vistas into the world outside of Israel or the Church. Creation gives us a sense of the world’s character and vocation. It does the same for the human person—all persons. It sketches the character of the end times. And most significantly it describes a world, its Creator, and the human drama that is big enough to contemplate and respond to the otherwise unthinkable catastrophe of climate change and mass extinction.