Is My Work Pointless?

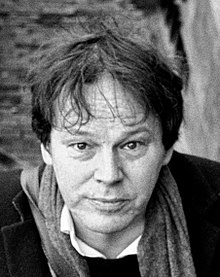

I’ve just discovered David Graeber, the American-born London School of Economics professor of Anthropology. And political gadfly. Graeber is enjoying notoriety for his 2012 book, Debt: The First 5000 Years, which turns up consistently on anthropology must-read lists. As I was googling around for all things “David Graeber” his now-viral expression, “bullshit jobs,” grabbed my attention.

Graeber has noticed, even in casual chit chat, that people are often embarrassed by what they do 9 to 5 each day. As he dug into what people were actually doing 40 hours a week he was struck by how much work served no social purpose. Graeber estimates that 70% of American jobs provide no community benefit. They are work for the sake of work. And, yes, they are paid jobs.

Graeber has had this idea for some time and first published it in little-known Strike Magazine. The essay exploded in popularity and laid the foundation for a whole new book, Bullshit Jobs: A Theory.

Graeber is saying that the mechanization of traditional work in agriculture, home-keeping, and construction has freed lots of people to work in service-administrative jobs. . He identifies five categories of BS jobs: flunky jobs, (receptionists who make bosses look like bosses), goons (corporate lawyers, telemarketers) duct tapers (people who patch problems that businesses don’t want to fix), box tickers (people who get ready to do important work rather than actually doing important work), and task masters (middle managers). The movie, “Office Space,” is a hilarious exploration of most of these categories.

Incidently, the Gallup Polling Organization has been attempting to measure the workplace phenomenon of employee “engagement.” They have come up with eye-popping statistics about the amount of goofing off that can take place at one’s desk and how many employees admit to stretching three or four hours of real productivity into a whole day or whole week. Lack of engagement may be a what happens when workers decide that what they are doing is unimportant.

Whatever Happened to Work?

For me, Graeber’s proposal shines a light on the Book of Genesis’ idea that, in a fallen world, something awful has happened to work. Adam and Eve ate the forbidden fruit and their relationship with God ruptured and became complicated. The human’s easy living in the Garden gave way to struggle. Work seems to have suffered:

And to the man he said,

‘Because you have listened to the voice of your wife,

and have eaten of the tree

about which I commanded you,

“You shall not eat of it”,

cursed is the ground because of you;

in toil you shall eat of it all the days of your life;

thorns and thistles it shall bring forth for you;

and you shall eat the plants of the field.

By the sweat of your face

you shall eat bread

until you return to the ground,

for out of it you were taken;

you are dust,

and to dust you shall return.’ —Genesis 3:17-19

The Bible tells the story of how God fixes the messed-up situation that resulted from that first disobedience. If we scroll forward to the New Testament and Jesus’ coming, or more specifically, the coming of the Kingdom of God, human work is restored to its original wholesomeness.

Jesus remarks, “The harvest is plentiful, but the laborers are few; therefore ask the Lord of the harvest to send out laborers into his harvest.” (Matthew 9:37-38) Nothing is more urgent than a field laden of standing grain ready to be gathered. The planter is desperate to get enough hands into the field to cash in on all of his work of planting and tending.

No bullshit work here. No unemployment either. Generally, Jesus uses the image of planting as something God does. Harvesting requires human helpers. And because the image of the harvest is an important metaphor for the mission of the Christian community, we have in this one saying of Jesus an indicator of what the entire New Testament is saying about human work. It’s abundant and important.

One of Jesus’ provocative parables is the story of the Workers in the Vineyard. Matthew 20:1-16 This parable depicts God as a landowner who is trying to hire farm laborers, who have gathered in the marketplace seeking work. Sermons about this parable tend to focus on the story’s conclusion when the landowner pays each of the workers a full day’s wage even if they had only been on the job for an hour or two. That generosity is certainly a puzzle.

Just as interesting, however, is that the landowner’s repeated trips back to the marketplace to find more and more workers to go into his field. He’s putting people on his payroll an hour before sundown. For some reason the landowner is fixated on getting as many workers as possible into the field and paychecks in everybody’s’ hand. This story points to a restored or even glorified state of work in the Kingdom of God.

Every Job Indispensable

A final example that supports the view that work, the tasks that God is directing his people to do, is always sufficient, always important, and always prized in God’s eyes. The Apostle Paul’s image of the church as body expresses these principles. In the same way that no body part is dispensable, so every member of a Christian community is functional and indispensible.

…Every member of a Christian community is…indispensible…

The idea, which appears in a couple of Paul’s letters (Romans 12.3-8; I Corinthians 12.14-26) is that a Christian community is as much organism as organization. Hand, eye, feet, ears function differently. But each is important. Individuals have different jobs. No jobs are pointless or goof-off worthy.

One of the big themes in Jesus’ teaching, a theme that is enjoying a comeback in churches nowadays, is the confidence that a new order, the Kingdom of God, is encroaching upon the world.

It’s similar to the situation where an investor buys a business. The employees don’t notice a change at first. The hourly janitor who pushes a broom all day, the woman who answers the phone, the warehouse worker who operates the forklift all report for work at 7:00 a.m. Nothing may seem different at first. But soon policies and strategies began to have a fresh feel. In a year or so paychecks improve. Stupid conflicts disappear. The change in owners makes the business a fun place to work for again.

Part of the beauty of the Christian life is that it restores the disciple’s relationship with work.

No, it will not change a pointless job. But it will incorporate into our lives meaningful work that can be carried out all day long. People around us need friends and a listening ear. Good news needs to be shared. Children need to be taught. The harvest is still plentiful.

What About My Job?

I find Graeber amusing and I love his irreverence for the secular work place. He also nudges me to wonder about the value of what I’ve worked at through my life. What have I contributed? Of the various tasks that I perform, which ones matter? Housework? Writing? Should I be doing ministry with a congregation? What about prayer? Study? Socializing? Neighborhood and political voluntarism?

Karl Barth’s idea rushes in as part of the answer: “To clasp the hands in prayer is the beginning of an uprising against the disorder of the world.”